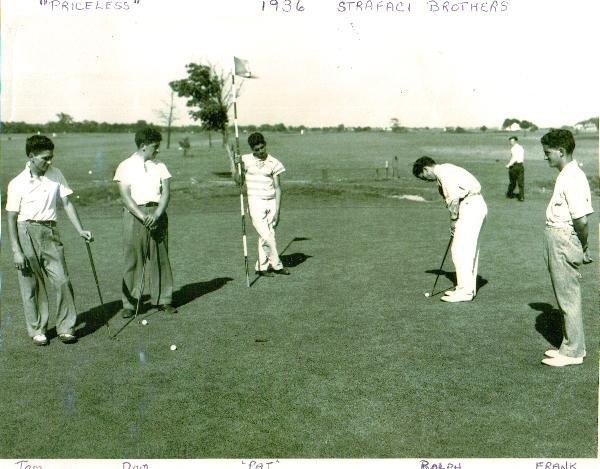

Frank Strafaci, probably at Doral, where he became the director of golf in 1960.

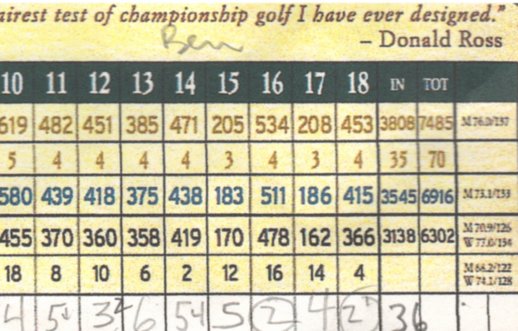

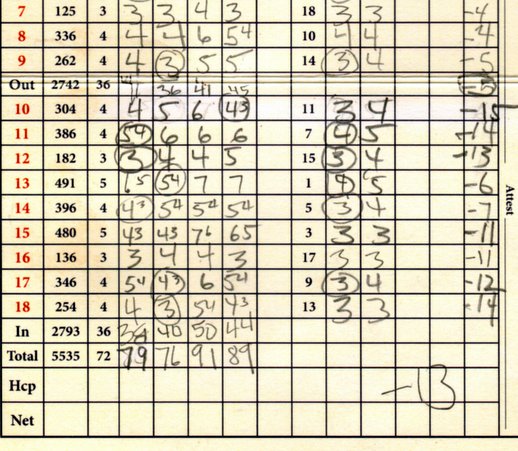

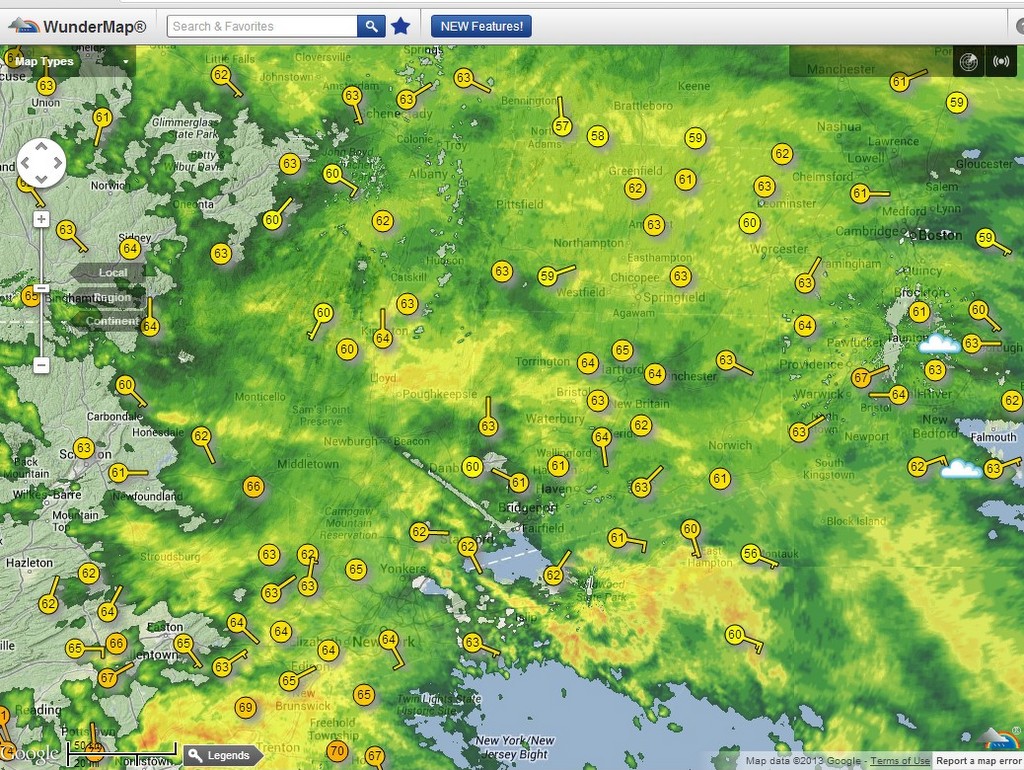

On Sunday, seven of my friends and I left home at 4:30 a.m. so that we could drive to Brooklyn in time to play Dyker Beach Golf Course with members of Shore View Golf Club. I’ve written about Dyker and Shore View a couple of times recently, and I’ll have more to say about them in an upcoming Golf Digest column.

During our round at Dyker, I learned about the Strafacis, a historically significant Brooklyn golf family, and today I learned more. There were five Strafaci brothers, all talented players. The most accomplished was Frank, who won the U.S. Amateur Public Links Championship (on the thirty-seventh hole) in 1935, when he was nineteen. (He was described by the Brooklyn Eagle as “curly-haired little Frankie Strafaci.”) He finished ninth in the 1937 U.S. Open, ahead of Gene Sarazen, Jimmy Demaret, and Byron Nelson, among others, and that performance earned him an invitation to the 1938 Masters, from which he withdrew after three rounds. He was playing poorly and the tournament had been delayed by rain, and he knew that if he stayed for the fourth round he wouldn’t be able to qualify for the North and South Amateur—which he then won, both that year and the next.

Frank Strafaci and Bobby Dunkleberger, following the former’s defeat of the latter on the thirty-sixth hole of the final match of the 1939 North and South, Pinehurst, North Carolina.

During the Second World War, Strafaci was a technical sergeant in the Army’s DUKW Command, which handled amphibious transport. He took part in the Battle of the Philippines, in 1944, and on the second day was pinned behind a tree by Japanese snipers. Shortly afterward, he described the experience in a letter to Morton Bogue, the president of the U.S.G.A.:

I couldn’t see them and so I held my fire, and it was at this time that I got to thinking of the five foot putt I had to make to tie the 8th hole in an exhibition golf match played in Brisbane only a few weeks ago (Captain Bud Ward came down from Dutch New Guinea for five days, and I arranged a match for the benefit of the Australian Red Cross, which we lost 3-2). Our opponents, Alex College and Dick Coogan, played a bit too good for us. I thought of what a tough spot we would have been in if I missed the putt. I can assure you I’ll never try hard for another putt for as long as I live, at least it won’t seem like trying.

The U.S.G.A. had sent a shipment of golf balls to the Red Cross in Australia, as a morale-booster, and Strafaci thanked Bogue. He also wrote:

[When] I get back to the States I hope to present the USGA with a golf ball that has already traveled over 43,000 miles and been used for 52 rounds of golf. It was used in America, Australia, Dutch New Guinea, I expect soon to use it in the Philippines, China and Japan. I used it for the first time at my club Sound View, and from there it went to Omaha, back to Sound View then to Frisco, Adelaide, Australia, Melbourne, Townsville, Cairns, Sydney, Cairns, Brisbane, Cairns, Brisbane, Dutch New Guinea (I didn’t have a club, I batted it around with a club made out of a branch.)

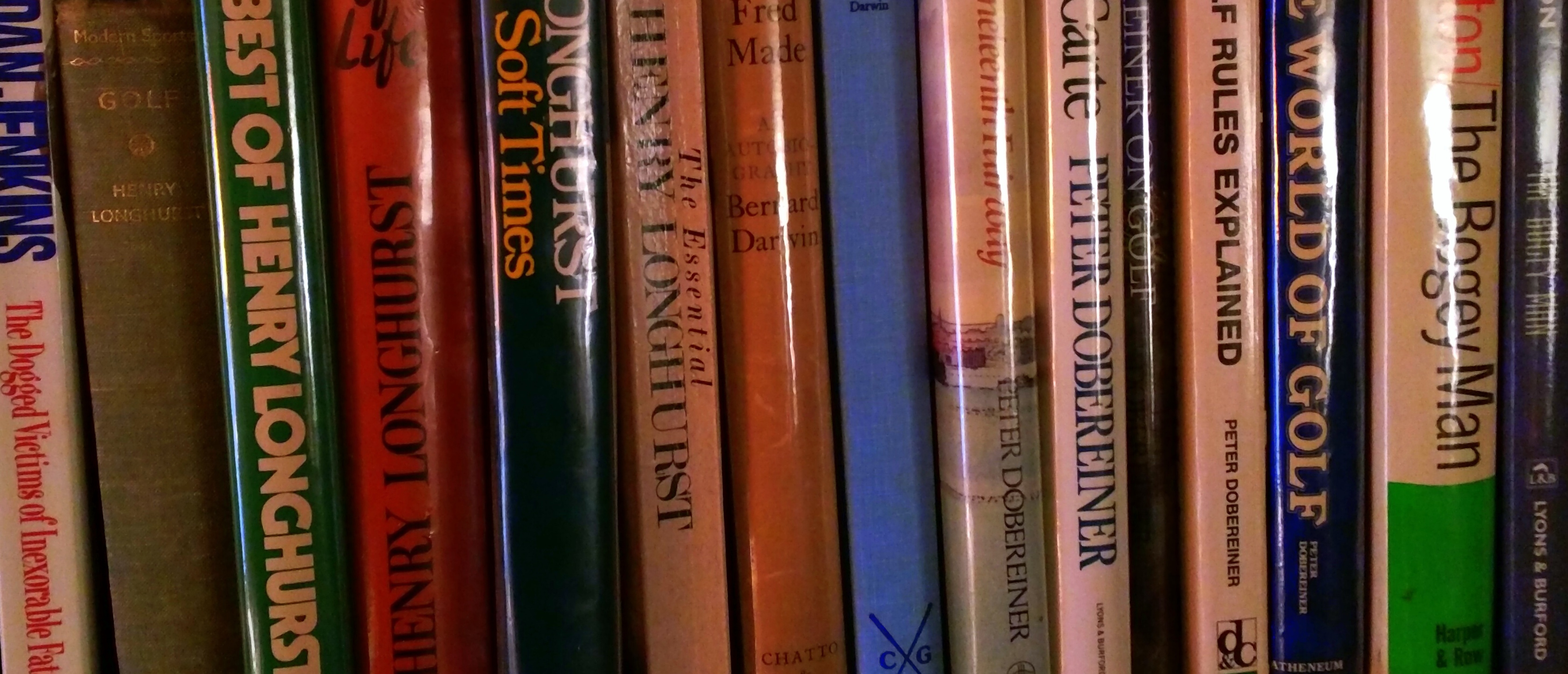

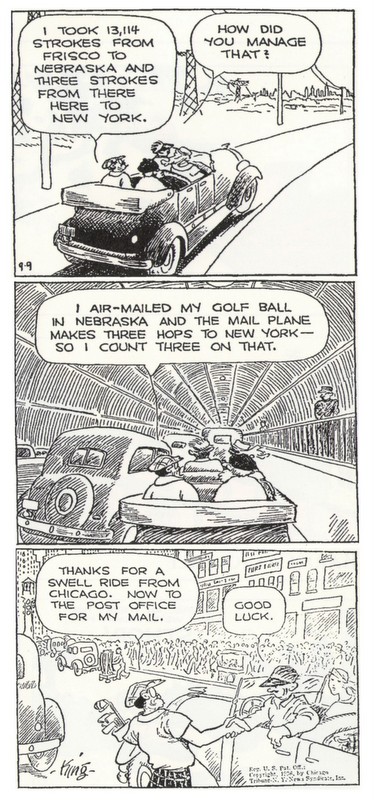

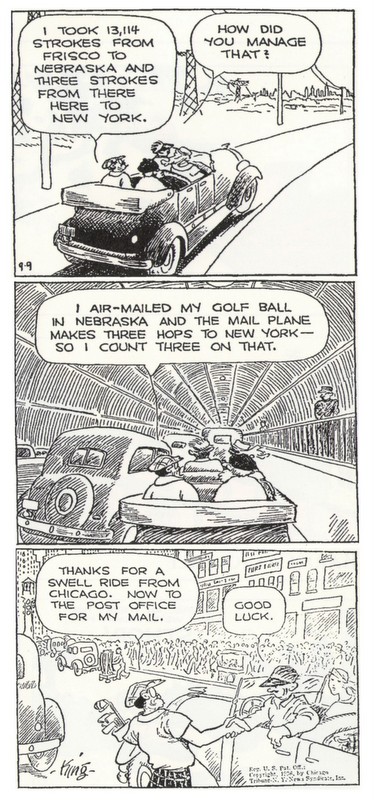

Dan Hubbard, who works in the communications department of the U.S.G.A. and, as it happens, is a member of my club, told me in an email: “We do not have a record of a golf ball coming in from Frank Strafaci, but we do have a five-peso bill issued by the Japanese government from the Philippines which he sent to Morton Bogue from Leyte in April of 1945.” Strafaci’s inspiration for his long-distance ball stunt may have been a series of cartoons in 1936 by Frank King, in his syndicated strip Gasoline Alley. In that series, Doc sets out to play a golf ball from San Francisco to New York—and in the strip below he’s nearing his goal:

In subsequent installments, Doc “breaks 80” between the post office and the East River, and finishes with a transcontinental score of 14,197. (In 1927, according to the book Golf in the Comic Strips, “a plumber and golfer by the name of Joe Grahame set out to achieve the same goal. He disappeared somewhere in the middle of Texas.”)

Strafaci played in a second Masters, in 1950, and he lost to Arnold Palmer on the eighteenth hole in the first match-play round in the 1954 U.S. Amateur. Palmer, who went on to win (and then to turn pro), said his match with Strafaci had been his toughest in the tournament. Strafaci became the director of golf at Doral in 1960, and named the Blue Monster. He died in 1988.

Frank’s father, Joseph Strafaci, owned a small farm that included the site now occupied by the Dyker clubhouse. Frank’s brother Thomas, and Thomas’s son Thomas, Jr., served as Dyker’s head professionals from 1958 until 1983. Frank’s grandnephew Paul is a recent past president of Shore View—the fifth Strafaci to hold that position—and a highly decorated New York City detective. Paul and a brother—another Frank—were members of the golf team at St. John’s University in the nineteen-eighties. And Jill Strafaci, who is the wife of Paul’s cousin Frank (the son of the one who tested Arnold Palmer), was a star golfer at the University of Florida and, later, an executive in the Miami Dolphins organization. Her husband was an executive of the Florida State Golf Association and is now a member of its advisory board.

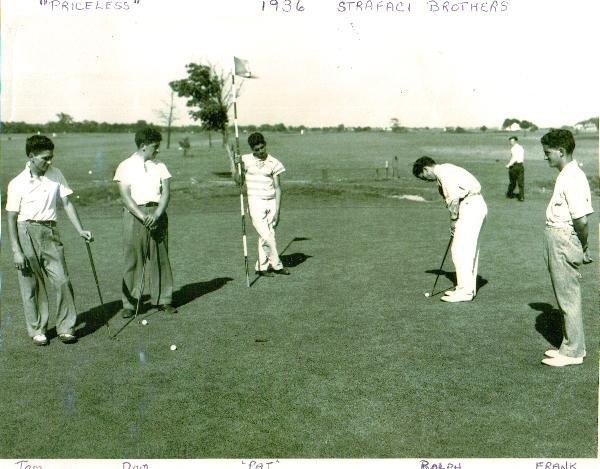

The fivesome in the photo below—which was taken in Queens in 1936, possibly at Oakland Golf Club, which was redesigned Seth Raynor in 1915 but buried by expressways in 1952 and 1960—consists of the five Strafaci brothers. From left to right they are Thomas, Dominick, Pasquale, Ralph, and Frank.