Bob Hacker, my best golf buddy for almost thirty years, died this week. I wrote about him many times in this blog and in Golf Digest, where he was always “Hacker (real name),” and I wrote about him once in The New Yorker, where he was just Bob Hacker. Most of my happiest memories in golf have involved him, in one way or another.

When I joined my golf club, in the early nineties, the main organized competitions were weekend scrambles. Many of the men who played in them were oldish high-handicappers, and their main contribution to their scramble teams, after slicing their hundred-and-fifty-yard drives out of bounds, was offering unsolicited instructional advice. (“Would you mind if I told you something about your weight shift?”) In 1996, a group of us mostly younger guys decided that we’d been good sports for long enough. We got together, unofficially, early one Sunday morning, and made teams by drawing balls from someone’s hat. Then we did it again the next Sunday—and the next, and the next—and we’re still doing it, although we now draw numbered poker chips instead of balls. We call our Sunday-morning group the Sunday Morning Group. It’s an unimaginative name but an occasionally useful one, because it sounds less like golf than like Bible study. There are more than seventy guys on our email list, ranging in age from late teens to late eighties. On a typical Sunday morning, twenty or thirty show up. We take turns bringing lunch.

The Sunday Morning Group is governed by the Committee, whose decisions are not reviewable. From S.M.G.’s founding until a few years ago, the Committee was Bob, who, in addition of having the best golf name of any golfer I’ve ever known, devised and enforced our short list of inviolable rules: “no handicap strokes on par 3s,” “no more than one handicap stroke on any hole,” “money never flows backward.” The first two of those rules were meant to discourage the choppers who had tormented us in the scrambles, although, technically speaking, everyone has always been welcome.

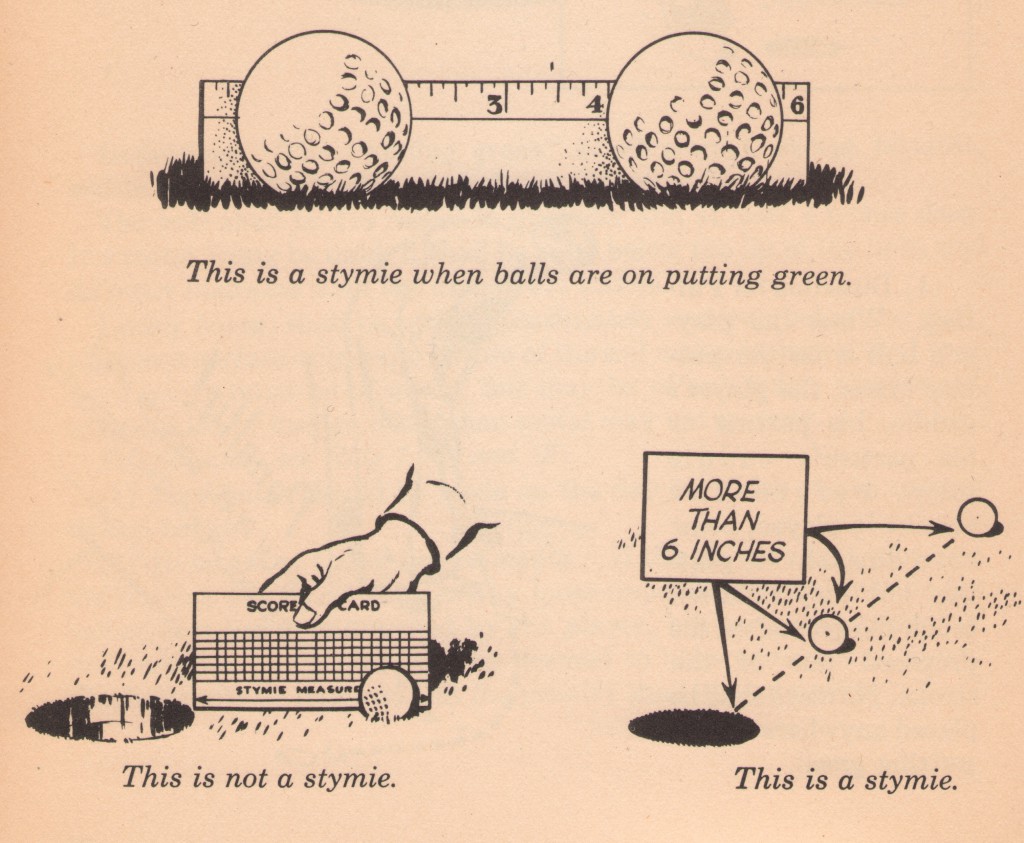

Bob also organized most of our extracurricular activities, including our annual autumn trips to Atlantic City and our occasional late-summer night-golf tournaments, played with glowing balls. For several years, he ran a supplemental weekly nine-hole league. Every Tuesday afternoon, he would announce, by email, a unique condition for that evening’s competition: one-stroke penalty for every practice swing or waggle, driver required from every tee, driver forbidden on any tee, stymie rule in effect, play five and six twice but count only your better scores. Bob also supervised our one and only S.M.G. overnight—the one that nearly got four of us thrown out of the club (long story). Those who slept at all that night mostly did so in our cars. We were awakened, shortly after dawn, by the smell of the many pounds of bacon that Bob was frying on the club’s propane grill.

In addition to everything else, Bob did all of S.M.G.’s bookkeeping. He took his responsibilities so seriously that, when he once mislaid the day’s scoring records, during one of our Atlantic City trips, he stayed up most of the night recreating them from our scorecards. (He found his folder the next day, in his car.) He was always ready to play. During a trip to Pinehurst one spring, he got up with the sun, took a shower, woke up his roommate and told him to take a shower, and went downstairs in the house where everyone was staying. A few of us were watching TV and drinking beer. “Kind of early for that, isn’t it, guys?” he said. But it wasn’t. It was just a little past midnight, maybe an hour after Bob and his roommate had gone to bed. He was so eager to get back to golf that he had mistaken the streetlight outside his window for the sun.

Bob spent most of his non-golf career in construction. A guy whose house he built was a member of Pine Valley but didn’t have any friends; once or twice a year he would invite Bob to come down and bring six of his own friends. I got to go on quite a few of those trips—even though, during one of them, I T-boned the Mercedes of the man who until recently had been Pine Valley’s Committee, the club’s legendarily fearsome immediate past chairman, Ernie Ransome (another long story).

Until a few years ago, Bob seemed indestructible. One Sunday morning many years ago, he felt a twinge in his chest as he was hitting an explosion shot from the bunker in front of our eighteenth green. He drank a couple of beers with the guys, then went home and mowed his lawn. Only after he had finished the yard did he drive himself to the hospital and learn that he’d had a heart attack. Ten or fifteen years later, he tore a rotator cuff. Instead of having surgery, which would have benched him for the rest of the season, he invented a golf swing that didn’t require the full participation of both arms. But that injury and a couple of others, plus the well-known toll of time, eventually caught up with him. His orthopedist told him that he couldn’t put off surgery any longer and that, what’s more, he needed work on the other shoulder, as well. The year before the pandemic, Bob took a medical leave of absence, and not long after doing that he broke a couple of ribs. Everyone hoped that he’d be back the next year, but Bob himself was skeptical. He never played golf again.

Bob’s role as the Committee was taken over by Fritz, who is roughly the age that Bob was when S.M.G. began, and his role as our statistician has been taken over by Jimmy, who is much younger. Fritz has modified a few of our ancient rules—as is the prerogative of the Committee. The changes are really a kindness to the group’s founding members, who are now roughly the age of the members we were trying to avoid in 1996. We now give strokes on par 3s (though just half-strokes count toward skins on those holes) and you no longer have to be present at lunch in order to receive money for skins. Both of those changes are viewed by almost everyone as improvements over the old ways. But Fritz himself would be the first to say that if he’s been able to see farther it’s only because he’s standing on the shoulders of a giant.