I have a piece about LIV Golf on The New Yorker’s website. You can read it here.

I have a piece about LIV Golf on The New Yorker’s website. You can read it here.

Bob Hacker, my best golf buddy for almost thirty years, died this week. I wrote about him many times in this blog and in Golf Digest, where he was always “Hacker (real name),” and I wrote about him once in The New Yorker, where he was just Bob Hacker. Most of my happiest memories in golf have involved him, in one way or another.

When I joined my golf club, in the early nineties, the main organized competitions were weekend scrambles. Many of the men who played in them were oldish high-handicappers, and their main contribution to their scramble teams, after slicing their hundred-and-fifty-yard drives out of bounds, was offering unsolicited instructional advice. (“Would you mind if I told you something about your weight shift?”) In 1996, a group of us mostly younger guys decided that we’d been good sports for long enough. We got together, unofficially, early one Sunday morning, and made teams by drawing balls from someone’s hat. Then we did it again the next Sunday—and the next, and the next—and we’re still doing it, although we now draw numbered poker chips instead of balls. We call our Sunday-morning group the Sunday Morning Group. It’s an unimaginative name but an occasionally useful one, because it sounds less like golf than like Bible study. There are more than seventy guys on our email list, ranging in age from late teens to late eighties. On a typical Sunday morning, twenty or thirty show up. We take turns bringing lunch.

The Sunday Morning Group is governed by the Committee, whose decisions are not reviewable. From S.M.G.’s founding until a few years ago, the Committee was Bob, who, in addition of having the best golf name of any golfer I’ve ever known, devised and enforced our short list of inviolable rules: “no handicap strokes on par 3s,” “no more than one handicap stroke on any hole,” “money never flows backward.” The first two of those rules were meant to discourage the choppers who had tormented us in the scrambles, although, technically speaking, everyone has always been welcome.

Bob also organized most of our extracurricular activities, including our annual autumn trips to Atlantic City and our occasional late-summer night-golf tournaments, played with glowing balls. For several years, he ran a supplemental weekly nine-hole league. Every Tuesday afternoon, he would announce, by email, a unique condition for that evening’s competition: one-stroke penalty for every practice swing or waggle, driver required from every tee, driver forbidden on any tee, stymie rule in effect, play five and six twice but count only your better scores. Bob also supervised our one and only S.M.G. overnight—the one that nearly got four of us thrown out of the club (long story). Those who slept at all that night mostly did so in our cars. We were awakened, shortly after dawn, by the smell of the many pounds of bacon that Bob was frying on the club’s propane grill.

In addition to everything else, Bob did all of S.M.G.’s bookkeeping. He took his responsibilities so seriously that, when he once mislaid the day’s scoring records, during one of our Atlantic City trips, he stayed up most of the night recreating them from our scorecards. (He found his folder the next day, in his car.) He was always ready to play. During a trip to Pinehurst one spring, he got up with the sun, took a shower, woke up his roommate and told him to take a shower, and went downstairs in the house where everyone was staying. A few of us were watching TV and drinking beer. “Kind of early for that, isn’t it, guys?” he said. But it wasn’t. It was just a little past midnight, maybe an hour after Bob and his roommate had gone to bed. He was so eager to get back to golf that he had mistaken the streetlight outside his window for the sun.

Bob spent most of his non-golf career in construction. A guy whose house he built was a member of Pine Valley but didn’t have any friends; once or twice a year he would invite Bob to come down and bring six of his own friends. I got to go on quite a few of those trips—even though, during one of them, I T-boned the Mercedes of the man who until recently had been Pine Valley’s Committee, the club’s legendarily fearsome immediate past chairman, Ernie Ransome (another long story).

Until a few years ago, Bob seemed indestructible. One Sunday morning many years ago, he felt a twinge in his chest as he was hitting an explosion shot from the bunker in front of our eighteenth green. He drank a couple of beers with the guys, then went home and mowed his lawn. Only after he had finished the yard did he drive himself to the hospital and learn that he’d had a heart attack. Ten or fifteen years later, he tore a rotator cuff. Instead of having surgery, which would have benched him for the rest of the season, he invented a golf swing that didn’t require the full participation of both arms. But that injury and a couple of others, plus the well-known toll of time, eventually caught up with him. His orthopedist told him that he couldn’t put off surgery any longer and that, what’s more, he needed work on the other shoulder, as well. The year before the pandemic, Bob took a medical leave of absence, and not long after doing that he broke a couple of ribs. Everyone hoped that he’d be back the next year, but Bob himself was skeptical. He never played golf again.

Bob’s role as the Committee was taken over by Fritz, who is roughly the age that Bob was when S.M.G. began, and his role as our statistician has been taken over by Jimmy, who is much younger. Fritz has modified a few of our ancient rules—as is the prerogative of the Committee. The changes are really a kindness to the group’s founding members, who are now roughly the age of the members we were trying to avoid in 1996. We now give strokes on par 3s (though just half-strokes count toward skins on those holes) and you no longer have to be present at lunch in order to receive money for skins. Both of those changes are viewed by almost everyone as improvements over the old ways. But Fritz himself would be the first to say that if he’s been able to see farther it’s only because he’s standing on the shoulders of a giant.

I watched it in the boarding area of Augusta Regional Airport, on my way home from the tournament. I had company:

Watching the Masters on TV is what most reporters who cover the tournament do, incidentally. They don’t watch it at the airport, as I did; they watch it in Augusta National’s press building, which has such terrific technology (and so many free Krispy Kreme donuts) that they’re seldom tempted to go outside. Half a dozen years ago, I watched the final round of the Masters on a different TV, in the living room of a rented house in Augusta, with the late Dan Jenkins, who was even less likely than the average reporter to set foot on the golf course.

I did give the course a thorough, hole-by-hole inspection on Saturday. I was especially impressed by the changes to the fifth hole. The club has not only lengthened it significantly but also thoroughly reshaped the terrain, repositioned and reconfigured the bunkers, and added two thousand new trees and other plantings. Tiger’s victory seems all the more remarkable when you consider that he bogeyed the fifth all four days.

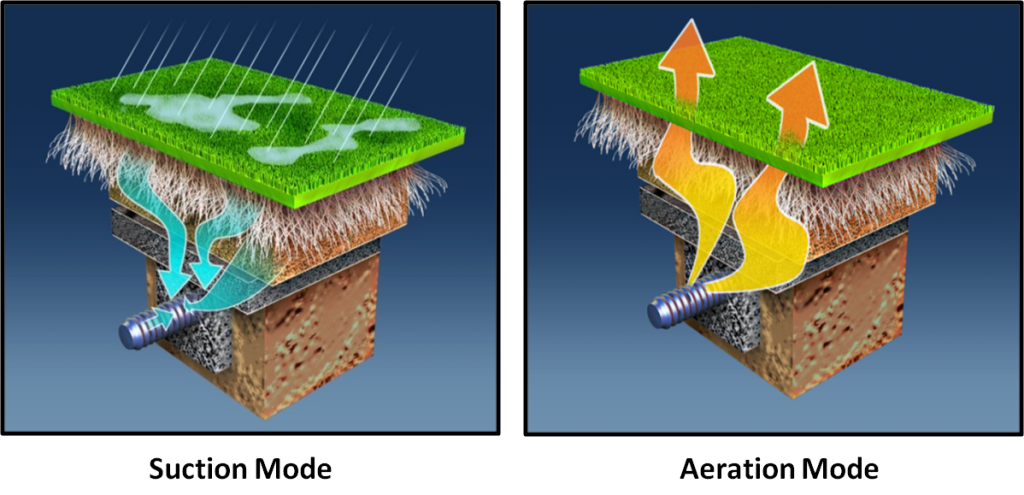

If you have the good fortune to watch the Masters in person this year, you may notice—as you wander the grounds with your mouth hanging open—that there are metal grates in a number of the greenside mounds. Those grates, and the mechanical hum that periodically emanates from them, are not proof that the tournament is a Matrix-like simulation created by green-jacketed aliens; instead, the grates provide ventilation for Augusta National’s extensive subterranean turf-conditioning system.

I saw an early version of that system while playing at the club in the late nineteen-nineties. A heavy rain had fallen during the night, and near one green I noticed a stove-size machine from which a torrent of water was gushing. A member explained that the system was called SubAir and that it had been invented a few years earlier by Marsh Benson, the club’s senior director of golf course and grounds. The machine I saw was attached to the existing network of drainage pipes beneath the putting surface and was acting like a giant Shop-Vac, hoovering moisture from below. In subsequent years, the club equipped all its greens with permanent, buried units—hence the grates. And it extended the system to much of the rest of the course

Slurping up downpours is actually not SubAir’s primary purpose—as I learned eight years ago from Kevin Crowe, who is the project director of the company that manufactures the systems. (SubAir’s headquarters are in Graniteville, SC, about fifteen miles from Augusta.) Benson’s primary original idea was to pump air into greens from underneath, and that’s what the units mainly do. “The concept is to supply fresh air into the root zone and help provide a more optimal growing environment for the plants,” Crowe explained. The first Augusta green to receive that treatment was the twelfth—a greenkeeping headache since the course was built—and Benson and his staff, after a couple of false starts, noticed rapid improvement in the health of the turf. Removing excess water, by operating in reverse, was secondary.

Is the investment worth it for other non-Augustas? The course architect Tom Doak has said that, during the planning for Sebonack Golf Club (which Doak designed with Jack Nicklaus), he offered “to quit the project” if the superintendent insisted on SubAir. Doak felt the system couldn’t possibly be useful in eastern Long Island, which is about as close as the United States comes to Scottish linksland. The director of construction education and technology for the USGA’s Green Section told me, “If you build greens properly, using our method, we don’t see a need for SubAir.” USGA greens are expensive enough as it is, he said, and their purpose is to provide exactly the kind of gas exchange and enhanced drainage that SubAir is meant to promote. Besides, he said, almost any golf course’s greens drain better, all by themselves, than its fairways or bunkers.

Still, hundreds of golf courses now have SubAir systems in one configuration or another, and Benson’s invention has found many applications outside of golf. The manager of field operations for the New York Mets once told me that he turns on his SubAir system each year in late February, five or six weeks before opening day. He also uses it to clean up after rainstorms and to ventilate the field when it’s covered for concerts. He doesn’t run it during games, however. “It’s loud,” he said, “and the louvers are right by the bullpens.”

Alex Nosevich, a reader and ad-agency partner in the Boston area, attended Monday’s practice round. Back in 2014, he described an October trip that he and a group of his friends had taken to Bethpage and Yale. This was his first trip to the Masters. His report:

The Masters and Augusta National are the Disney World of golf. Everything is perfect. There are few glimpses of any behind-the-scenes infrastructure. The one difference? All the employees and tournament workers seem genuinely happy and seem to want patrons to be genuinely happy as well.

Not to brag or anything, but as I walked by Zach Johnson’s caddie he said hi to me.

The players I saw were all business. Very few of them smiled or seemed to exchange pleasantries with each other. Well, one guy seemed to be having a great time: Tiger Woods was always smiling, even exchanging a fist bump with Fred Couples when they each knocked their shots on twelve to about three feet.

Rory outdrove D.J. by about ten yards on eight. D.J. must have hit his a groove too thin.

Rickie Fowler had a Tiger-in-his-prime following during his round.

The bathrooms are the unspoken highlight. There’s a greeter at the entrance who welcomes you to the Masters. There are two attendants inside who direct you to an empty stall, and they clean the toilet seat before the next patron enters.

The food is both highly overrated and highly underpriced. A chicken biscuit, a sausage biscuit, and a sweet tea (in a souvenir plastic cup) set me back eight dollars. And the biscuits were pretty good. An awesome deal. Lunch was also cheap—nine-fifty for the chicken sandwich, chips, and a Blue Moon ale—but the chicken sandwich was cold (should be warm) and pretty bland. Did not get to experience the pimento cheese sandwich. Hopefully I’ll win the ticket lottery next year and get to try it.

Augusta is not a very golfy town. It’s the capital of golf for one week per year, but, other than that, I don’t think most people there care very much about the game.

Two must-visit places to eat: Rhinehart’s Oyster Bar is an awesome fish shack/dive. Those with hygiene issues should probably eat outside. In fact, sit outside anyway. Had raw oysters (with plenty of horseradish) and a tasty catfish po’ boy.

The other place is the Whiskey Bar (Kitchen), in downtown Augusta. Huge selection of whiskey and heart-clogging burgers, plus my kind of vibe: hipster but not douchey. Loved the contrast during Masters week of seeing everyone wearing Titleist caps and polos in a place like that. Wore my Mr. Boh T-shirt and had more than a few Bawlmer folks chat me up.

The tournament workers are the friendliest, chattiest people ever. Talked with a few and it just made the experience that much more special. Even the security guards were helpful.

It’s amazing what you can accomplish with enough money, control, infrastructure and personnel.

Every building on the grounds is permanent. Not one tent in sight. No porta-potties. I think the grandstands and scoreboards and TV towers must be the only things that come down at the end of the event.

The hill along sixteen is one of the best spots to be during practice rounds. All the patrons chant for the players to skip their shots across the pond and onto the green, and all of them seem to oblige. Saw Tiger reach the green with his skipped shot.

Wish I could have had my phone to take pictures, but it’s nice to unplug for a few hours.

Lots of bird sounds, but no actual birds spotted. Creepy.

Thirteen is the greatest hole I have never played (and probably never will).

Amen Corner is everything it’s cracked up to be.

No celebrity sightings outside the ropes. Was hoping to catch a glimpse of Snoop Dogg at least. I did, however, run into some fellow Cyprian Keyes Golf Club members on twelve.

That approach into fifteen is scary.

Concessions and golf shop were incredibly efficient. In and out in no time.

The insane conditioning extends to the strip of grass between Berckmans Road and the sidewalks all around Augusta.

This is Rickie’s year for a green jacket. Trust me. I just won my March Madness pool, so I must know what I’m talking about. Right?

Scott Nixon was an insurance salesman in Augusta, Georgia. Between the early nineteen-thirties and late forties or early fifties, he visited several dozen American places called Augusta and documented their existence in a sixteen-minute silent film, called “The Augustas.” Nixon was a member of the Amateur Cinema League. “The Augustas” is preserved in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress and also in the University of South Carolina’s extraordinary Moving Image Research Collections. Benjamin Singleton, the production manager of the South Carolina collections, told me in an email, “Mr. Nixon traveled in his car all over the country, and sometimes went abroad with Mrs. Nixon. He liked to film trains, but, luckily, also visit the Masters and got a few good shots.”

Here’s a film Nixon shot at the Masters in the mid-fifties. Among many other things, you can pick out Jack Burke (red cardigan), Ben Hogan (that hat), and Bobby Jones and Clifford Roberts (riding in one of the first golf carts, first in the distance and then close-up).

And here’s footage Nixon shot of the Masters Parade—a tournament-week Augusta staple between 1957 and 1964. You’ll recognize at least a couple of faces in that one, too.

You can easily lose yourself in the Moving Image Research Collections, as I did both yesterday and the day before. Singleton told me, “The collection started in 1980. Twentieth Century Fox wanted to make a large corporate gift (probably worth about $100 million). They decided to give their Fox Newsreel films and all outtakes to the University of South Carolina. This was sixteen years before the advent of the Fox News cable channel. There is actually no continuity between Fox News and the Fox Newsreel. The newsreel ended in 1963 when it was sunk by television news. The original Fox News camera negatives are on the old nitrocellulose film stock. This film nitrate stock, related chemically to gun cotton, is flammable and difficult to extinguish when ignited. Nitrocellulose film was the cause of some sad movie theater fires back in the day. We can’t keep the film in city limits. We keep the nitrocellulose films in two WWII ammunition magazines at U.S. Fort Jackson, which in only a couple of miles from campus.”

One more Scott Nixon film from the Masters. Lots of stuff to explore while we wait for Round One.

The final-round duel between Maria Fassi and Jennifer Kupcho at the Augusta National Women’s Amateur was the awesomest golf of the year so far, not least because Kupcho began her amazing second-nine charge with a migraine that made it impossible for her to see clearly.

The day before, the Golf Channel ran a piece by Geoff Shackelford called “Three women who had a huge impact on Bobby Jones.” Marion Hollins is one of the three, and Shackelford’s piece includes some remarkable archival video (as well as an interview with me). Watch it here.

I just got back from Helsinki, where the golf season is even shorter than it is in New England. While I was away, The New Yorker‘s website ran a piece of mine about Marion Hollins, which you can read here. And you can watch silent footage of Hollins swinging a golf club at Pebble Beach in 1926 here, in a clip sent to me by Chris Buie.

I have an article in this week’s New Yorker about a golf school in a place where you wouldn’t expect to find one.

Mike B., Tim D., Rick, and I played at Fairchild Wheeler Golf Course today. The weather was actually pretty balmy, but the ground was frozen and we hit some monster drives. We also had trouble with the bunkers, even though they’d left the rakes.