I have an article in the summer issue of Links called “England’s Golf Coast.” It’s about a remarkable thirty-mile stretch of linksland that runs along the Lancashire coast between Liverpool and St. Annes, in northwestern England. The Golf Coast includes three of the ten courses on the active Open Championship Rota—Royal Liverpool, Royal Birkdale (where this year’s Open will be held), and Royal Lytham and St. Annes—but you could skip all three and still have an unforgettable trip. I’ve visited the area several times, most recently in 2013, and my friends have been talking about going back ever since our first trip there as a group, three years before that. The courses are so closely spaced that you can park yourself and your luggage in one place—no need for a coach and driver. In 2010, nine of us stayed mostly in three three-bedroom apartments in this building, in Southport:

The cost worked out to less than fifty dollars per man per night. The longest drive we had to golf was about an hour, and many of the courses we played were just a few minutes away. Here’s Barney in the living room of one of our apartments:

Below are photos of courses and people I mention in my Links article, taken during various trips over the years. First, St. Annes Old Links, which is next door to Royal Lytham and includes ground that was once part of its routing. Here are two members I played with. We wore rainsuits not because we expected rain but because the wind was blowing hard enough to shred ordinary golf clothing:

This is me in 2010 at West Lancashire Golf Club, known locally as West Lancs. It opened in 1873 and was the first Golf Coast course built north of the River Mersey. As is true of many courses in the area, you can travel to it by train from central Liverpool: A great guide to golf courses on the Lancashire coast is Links Along the Line, by Harry Foster, a retired teacher and a social historian. He rode along when I played Hesketh Golf Club, where he was a member for many years. (He died in 2014.)

A great guide to golf courses on the Lancashire coast is Links Along the Line, by Harry Foster, a retired teacher and a social historian. He rode along when I played Hesketh Golf Club, where he was a member for many years. (He died in 2014.) Hesketh isn’t my favorite course, but a couple of its oldest holes, on the second nine, are among my favorite holes. This view is back toward the clubhouse (the red-roofed white building near the center):

Hesketh isn’t my favorite course, but a couple of its oldest holes, on the second nine, are among my favorite holes. This view is back toward the clubhouse (the red-roofed white building near the center):

Hesketh has both a fascinating history (ask about the Hitler Tree) and a cool address:

In 2013, Foster and his wife joined me for dinner in the dining room at Formby Golf Club, one of my favorite courses anywhere. I actually spent several nights in the Formby clubhouse, in this room:

In 2013, Foster and his wife joined me for dinner in the dining room at Formby Golf Club, one of my favorite courses anywhere. I actually spent several nights in the Formby clubhouse, in this room:

The Formby course encircles a separate golf club, Formby Ladies. Don’t skip it, as I did until 2013, to my permanent regret. Among the women I played with was Anne Bromley, on the right in the photo below. Her father was once the head professional at Royal County Down:

The Formby course encircles a separate golf club, Formby Ladies. Don’t skip it, as I did until 2013, to my permanent regret. Among the women I played with was Anne Bromley, on the right in the photo below. Her father was once the head professional at Royal County Down:

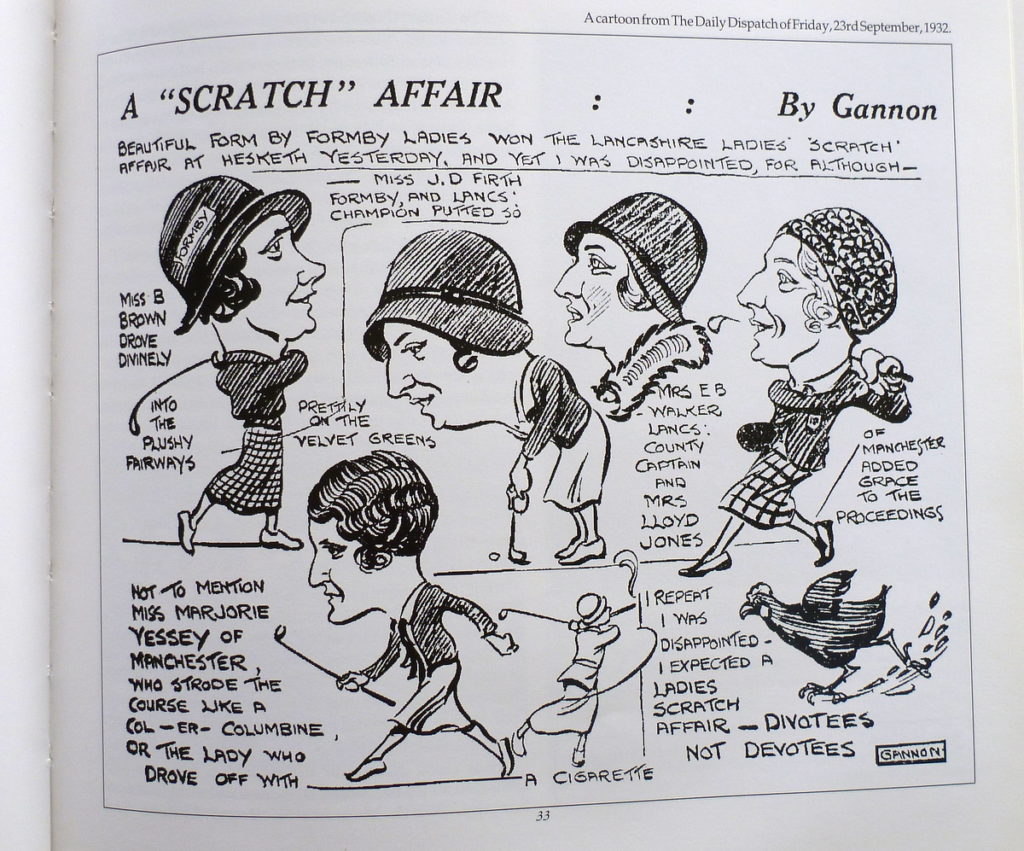

Formby Ladies isn’t long, but if you aren’t careful it will eat you up. The club has an excellent history, which you can study over lunch in the clubhouse (known to members as the Monkey House):

Formby Ladies isn’t long, but if you aren’t careful it will eat you up. The club has an excellent history, which you can study over lunch in the clubhouse (known to members as the Monkey House): At a nature preserve down the road from Formby, I met a retired Merseyside policeman and his wife, who own a coffee concession. He invited me to join him and his son, an aspiring professional, for a round at Southport & Ainsdale, which hosted the Ryder Cup in 1933 and 1937 and the British Amateur in 2005.

At a nature preserve down the road from Formby, I met a retired Merseyside policeman and his wife, who own a coffee concession. He invited me to join him and his son, an aspiring professional, for a round at Southport & Ainsdale, which hosted the Ryder Cup in 1933 and 1937 and the British Amateur in 2005. The first hole at S&A is a par 3, and it’s a corker:

The first hole at S&A is a par 3, and it’s a corker: Right next door to S&A, on the other side of the railroad tracks, is Hillside:

Right next door to S&A, on the other side of the railroad tracks, is Hillside:

And right next door to Hillside is Royal Birkdale, whose clubhouse was designed to look a little like an ocean liner:

And right next door to Hillside is Royal Birkdale, whose clubhouse was designed to look a little like an ocean liner:

Birkdale is one of my favorite Open courses. I played it with a young member who had a lot less trouble with it than I did. In fact, he shot pretty close to even par:

Birkdale is one of my favorite Open courses. I played it with a young member who had a lot less trouble with it than I did. In fact, he shot pretty close to even par:

In both 2010 and 2013, I spent one night in the Dormy House at Royal Lytham and St. Annes—part of a stay-and-play package that’s one of the greatest bargains in links golf. The view from my bedroom was across the practice green (and through mist) toward the clubhouse and the eighteenth hole: Here’s what the wind at Lytham—which wasn’t blowing when I took the photo below—has done to the trees. Many years ago, I wrote an article for Golf Digest whose opening line was “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows at Royal Lytham & St. Annes.” The copy editor, who had apparently never heard of Bob Dylan, changed “weatherman” to “weather report.” I was mortified, but it turned out that none of the magazine’s readers had heard of Bob Dylan either. Anyway, leave your umbrella at home:

Here’s what the wind at Lytham—which wasn’t blowing when I took the photo below—has done to the trees. Many years ago, I wrote an article for Golf Digest whose opening line was “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows at Royal Lytham & St. Annes.” The copy editor, who had apparently never heard of Bob Dylan, changed “weatherman” to “weather report.” I was mortified, but it turned out that none of the magazine’s readers had heard of Bob Dylan either. Anyway, leave your umbrella at home: You should play Royal Liverpool, of course, but don’t overlook Wallasey, just a few miles away:

You should play Royal Liverpool, of course, but don’t overlook Wallasey, just a few miles away: Wallasey was the home club of Dr. Frank Stableford, who in 1932 invented the round-rescuing scoring system that’s named for him. Here are the eighteenth green and the clubhouse:

Wallasey was the home club of Dr. Frank Stableford, who in 1932 invented the round-rescuing scoring system that’s named for him. Here are the eighteenth green and the clubhouse: And, of course, if you somehow get tired of playing golf you can take any of a number of interesting side trips:

And, of course, if you somehow get tired of playing golf you can take any of a number of interesting side trips: