Every October since 2000, the Sunday Morning Group has taken an end-of-season weekend golf trip to Atlantic City.

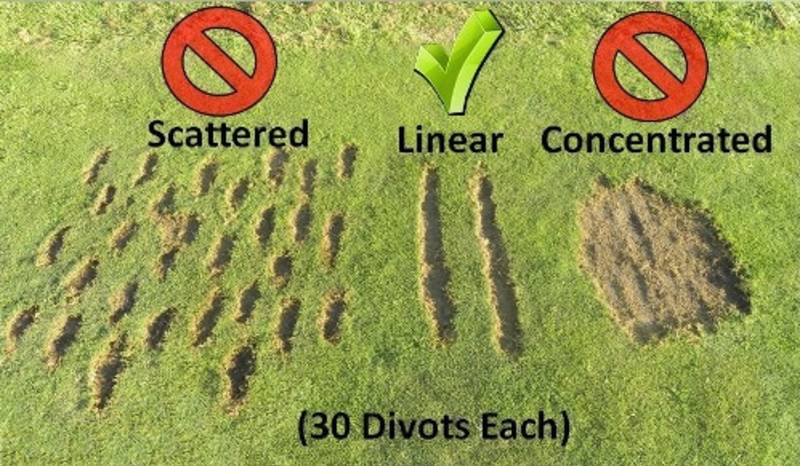

For the past four years, we’ve allowed every player on the trip to play from any set of tees. Some guys worried at first that our matches and team competitions would be unfair unless everyone was “playing the same course.” But we have discovered that, as long as you calculate the handicaps correctly, the competition actually works better if golfers are able to make rational decisions about the trade-off between course yardage and handicap strokes. And that’s true even when the skill spread is huge. (Handicaps this year ranged from 0 to more than 30.)

Our experience aligns perfectly with the findings of the USGA and the PGA of America, which in 2011 introduced Tee It Forward, an initiative that “encourages players to play from a set of tees best suited to their driving distance.” According to the USGA:

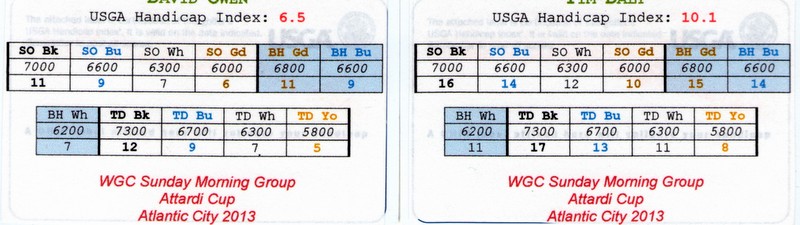

I firmly believe all of that. But there are reasons you haven’t heard much about Tee It Forward since 2011, and the main one is probably the USGA’s semi-incomprehensible two-step system for calculating course handicaps when players compete from different tees. Virtually no one understands how the USGA’s system works, including, in my experience, most PGA of America head professionals. My friends and I are able to do what we do mainly because Tim, who is SMG’s mathematician-in-residence, created an Excel spreadsheet that does all the figgerin’ in the background and eliminates a potentially huge rounding error inherent in the USGA’s method. Every player on the trip, before we leave home, receives a handicap for every set of tees on every course we’re going to play, and is then free to choose:

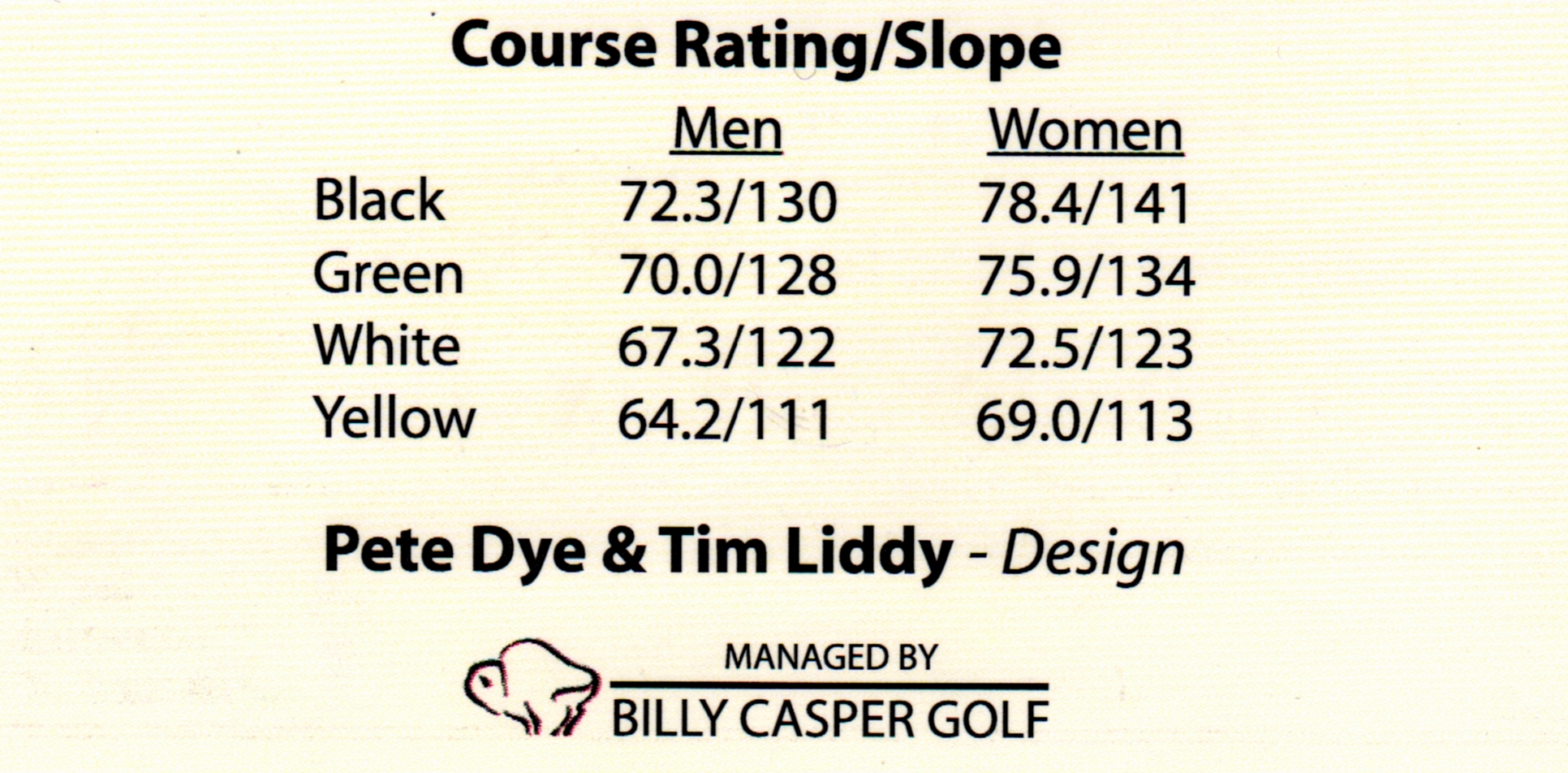

Another impediment to Teeing It Forward is that most golf courses stigmatize their forward tees by suggesting that they’re intended only for certain players — as at Twisted Dune, in Egg Harbor Township (a course we nevertheless all love):

It’s far, far better to rate all sets of tees for both men and women, and to give the tees gender-and-age-neutral names—as at Wintonbury Hills, in Bloomfield, Connecticut:

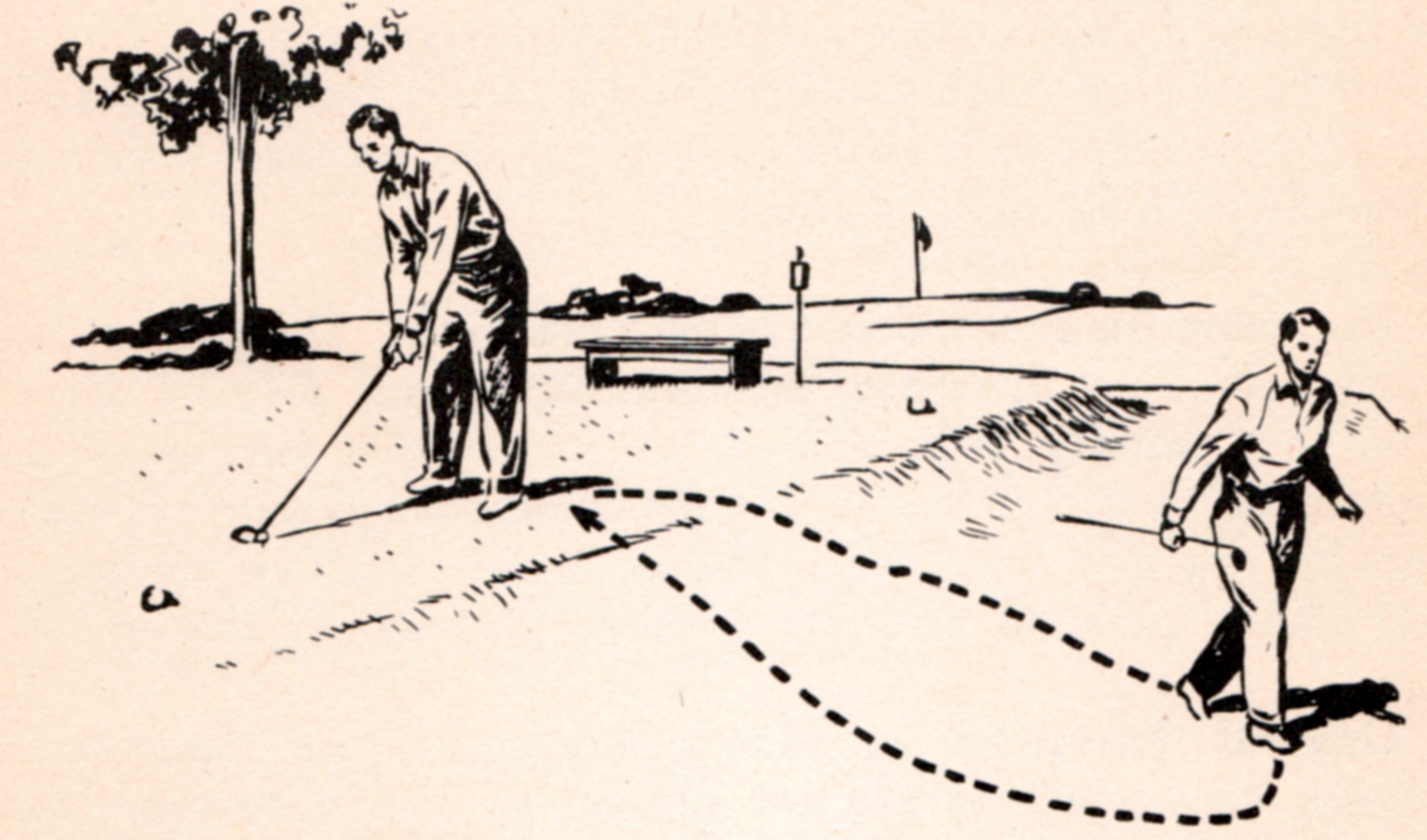

One discovery we’ve made during the past four years is that virtually all players, including many with single-digit handicaps, play better and have more fun if they move up — even way up. At Twisted Dune, Addison, who hits his driver 300 yards and has USGA Handicap Index of 0.4, played the black tees, from which the course measures 7,300 yards. But Brendan (8.3), Tim (12.3), and I (7.1) all played the “Senior Tees”—the yellows —from which the course is 1,500 yards shorter. When we started, Addison was so far behind us that we could barely see him. In the photo below, the red V is just above his head:

Addison loves playing from the tips, and he has more than enough game to do it. The rest of us, though, were very, very happy to move as far forward as we could.