I have a piece about LIV Golf on The New Yorker’s website. You can read it here.

I have a piece about LIV Golf on The New Yorker’s website. You can read it here.

I watched it in the boarding area of Augusta Regional Airport, on my way home from the tournament. I had company:

Watching the Masters on TV is what most reporters who cover the tournament do, incidentally. They don’t watch it at the airport, as I did; they watch it in Augusta National’s press building, which has such terrific technology (and so many free Krispy Kreme donuts) that they’re seldom tempted to go outside. Half a dozen years ago, I watched the final round of the Masters on a different TV, in the living room of a rented house in Augusta, with the late Dan Jenkins, who was even less likely than the average reporter to set foot on the golf course.

I did give the course a thorough, hole-by-hole inspection on Saturday. I was especially impressed by the changes to the fifth hole. The club has not only lengthened it significantly but also thoroughly reshaped the terrain, repositioned and reconfigured the bunkers, and added two thousand new trees and other plantings. Tiger’s victory seems all the more remarkable when you consider that he bogeyed the fifth all four days.

Scott Nixon was an insurance salesman in Augusta, Georgia. Between the early nineteen-thirties and late forties or early fifties, he visited several dozen American places called Augusta and documented their existence in a sixteen-minute silent film, called “The Augustas.” Nixon was a member of the Amateur Cinema League. “The Augustas” is preserved in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress and also in the University of South Carolina’s extraordinary Moving Image Research Collections. Benjamin Singleton, the production manager of the South Carolina collections, told me in an email, “Mr. Nixon traveled in his car all over the country, and sometimes went abroad with Mrs. Nixon. He liked to film trains, but, luckily, also visit the Masters and got a few good shots.”

Here’s a film Nixon shot at the Masters in the mid-fifties. Among many other things, you can pick out Jack Burke (red cardigan), Ben Hogan (that hat), and Bobby Jones and Clifford Roberts (riding in one of the first golf carts, first in the distance and then close-up).

And here’s footage Nixon shot of the Masters Parade—a tournament-week Augusta staple between 1957 and 1964. You’ll recognize at least a couple of faces in that one, too.

You can easily lose yourself in the Moving Image Research Collections, as I did both yesterday and the day before. Singleton told me, “The collection started in 1980. Twentieth Century Fox wanted to make a large corporate gift (probably worth about $100 million). They decided to give their Fox Newsreel films and all outtakes to the University of South Carolina. This was sixteen years before the advent of the Fox News cable channel. There is actually no continuity between Fox News and the Fox Newsreel. The newsreel ended in 1963 when it was sunk by television news. The original Fox News camera negatives are on the old nitrocellulose film stock. This film nitrate stock, related chemically to gun cotton, is flammable and difficult to extinguish when ignited. Nitrocellulose film was the cause of some sad movie theater fires back in the day. We can’t keep the film in city limits. We keep the nitrocellulose films in two WWII ammunition magazines at U.S. Fort Jackson, which in only a couple of miles from campus.”

One more Scott Nixon film from the Masters. Lots of stuff to explore while we wait for Round One.

I have an article in this week’s New Yorker about a golf school in a place where you wouldn’t expect to find one.

Mike B., Tim D., Rick, and I played at Fairchild Wheeler Golf Course today. The weather was actually pretty balmy, but the ground was frozen and we hit some monster drives. We also had trouble with the bunkers, even though they’d left the rakes.

I have a little essay on the New Yorker’s website about golf’s new rules. A new rule I didn’t mention is the one about taking drops. Like the new rules about what used to be called hazards but are now called penalty areas, it seems to address a rules-committee disagreement rather than a golf problem.

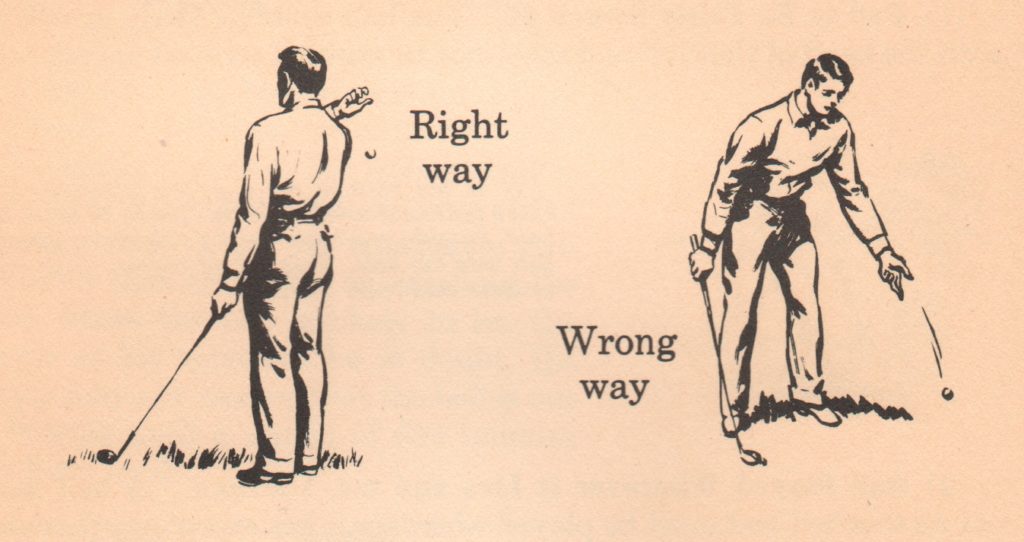

When the Gentlemen Golfers of Leith, in 1744, hit balls “among watter, or any wattery filth,” they were allowed to remove the balls, at the cost of a stroke, and tee them up behind the hazard (using little mounds of dirt—not wooden pegs, which hadn’t been invented yet). A decade later, the Society of St. Andrews Golfers required that such balls be thrown behind the hazard, “six yards at least.” In 1776, the Edinburgh Burgess Golfing Society stipulated that the throw be made “over your head, behind the water,” and in 1809 the competing Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers replaced throwing with dropping. In subsequent years, dropping over the head evolved into dropping over the shoulder, and it stayed that way until 1984, when the U.S.G.A. and the R. & A. first allowed golfers to aim their drops, by making them at arm’s length from shoulder height. There was discussion, while the current revisions were being weighed, about allowing golfers to drop balls from as little as an inch or two above the ground; the rule as adopted requires that balls be dropped from the height of the knee—a compromise whose only real effect is to demonstrate that a compromise was reached. The simplest solution would have been to allow players to do what they’ve long been required to do in certain relief situations: to simply place their ball on the ground.

The golf dream I wrote about in my previous post appears to be an example of a universal type. (See the comments—and I’d be happy to hear about others.) Here’s a similar one I had, almost twenty-five years ago:

I was getting ready to tee off on a 193-yard par three on a fancy country-club course that I knew nothing about. The first player to hit used a nine-iron. His ball cut low between two big maple trees, threaded its way through a partly opened wrought-iron gate in a high stone wall, and landed pin-high on a green the size of a mattress. There were some cars parked near the green, and, in fact, the green sometimes seemed to be situated in an empty parking space on a crowded city street. It was now my turn to hit, and I felt embarrassed that I was going to have to use a three-iron after the first player, whom I didn’t seem to know, had used a nine. I had a great deal of trouble finding a place to tee my ball, because half a dozen golfers were sitting in large armchairs arranged haphazardly on the tee. They were laughing and talking loudly, and paying no attention to me. As I moved anxiously among them, I was also somehow crawling near the green, and I found several balls hidden in some thick rough. I seemed to know that one of these balls belonged to the first player, and I believed that by studying it closely I would learn something that might help me with my own shot. I was having trouble concentrating, because I was worried about something the first player had done before teeing off. He had teed his ball three club lengths behind the tee markers, a distance he had measured with his club, and while I crawled among the big chairs I tried to decide whether I should inform him that the rules of golf permit teeing the ball no more than two club lengths behind the tee markers. I was worried that my concern about his violation of the rules would affect my ability to hit my own shot. My struggle seemed to go on for a very long time. Before I got around to hitting my ball, I woke up.

My first driver—which was partly responsible for my decision, at the age of thirteen, to give up golf for more than twenty years—was a two-generation hand-me-down with a head that could have filled in as the foot of a Queen Anne chair. Nowadays, though, even seven-year-olds demand titanium. A few years ago, I played in a senior event with a guy from another club who carried an ancient Spalding persimmon 3-wood, but he was the only Luddite in the field and he never hit a good shot with it. Golfers who still use clubs with wooden heads are invariably older than seventy, and they are stubborn, cheap, ignorant, or a combination of all three. You seldom see actual wood anymore even in the golf bags of estranged wives, who occupy the lowest rung on the club recycling ladder.

The question, though, is whether this change in technology necessitates a change in terminology. Various prominent television commentators, Johnny Miller among them, have decided that it does. They refer to woods as “metals,” saying, for example, that a certain player has elected to go for the green with a “fairway metal” of some kind—perhaps a “3-metal.” Jim Nantz, on CBS, sometimes refers to a fairway wood generically as “a metal-headed club.”

There are three things wrong with this trend. The first is that it creates more confusion than it eliminates, since almost all modern golf clubs, including irons and putters, are “metal-headed.” The second is that “wood” is no more anachronistic than “iron.” (Irons haven’t been made of iron since Britain was ruled by Romans. Should we start calling those clubs “alloys”?) The third is that avoiding “wood” is excessively fastidious, like objecting to the use of the (useful) word “hopefully.” The television commentators are proposing a solution for a problem that doesn’t exist.

Besides, retaining an archaic expression creates the possibility for creative revisionism later on.

“Why are woods called ‘woods’?” your great-great-granddaughter may ask you someday.

“Well, Little One,” you can explain, “there was an awfully good player back around the turn of the century. He hit the ball farther than anybody else, and he won every prize there was to win. In fact, I taught him everything he knew. Woods were named after him.”

The great English humorist P. G. Wodehouse—the creator of Jeeves, Wooster, and Psmith, among numerous other unforgettable characters—wrote two dozen stories about golf, most of them featuring the Oldest Member, who no longer plays but haunts the clubhouse at Marvis Bay Golf and Country Club and, once he has begun reminiscing and philosophizing, can’t be stopped. Wodehouse published 19 of the stories in two golf-only volumes, The Clicking of Cuthbert and The Heart of a Goof.

The Overlook Press, which for 45 years has specialized in books that other publishers have paid insufficient attention to, has re-published both volumes in an attractive boxed set. Wodehouse should be considered mandatory reading for all serious golfers, and the boxed set makes an especially appealing gift because it is perfectly rectangular and therefore easy to wrap.

A sample, from “The Heel of Achilles”:

Golf is in its essence a simple game. You laugh in a sharp, bitter, barking manner when I say this, but nevertheless it is true. Where the average man goes wrong is in making the game difficult for himself. Observe the non-player, the man who walks round with you for the sake of the fresh air. He will hole out with a single care-free flick of his umbrella the twenty-foot putt over which you would ponder and hesitate for a full minute before sending it right off the line. . . . A man who could retain through his golfing career the almost scornful confidence of the non-player would be unbeatable. Fortunately such an attitude of mind is beyond the scope of human nature.

Overlook offers other Wodehouse sets, too. It has also republished, in paperback, the entire oeuvre of Charles Portis, whose (golf-free) 1979 masterpiece, The Dog of the South, is the funniest American novel since Huckleberry Finn. Better buy two of everything, in case no one thinks of giving them to you.

home course has a terrific practice area, which our greens crew has built and steadily improved over many years. Here are Corey (our pro, left) and Gary (our superintendent) last March, in the rain. They’re measuring yardages from various positions on the freshly re-graded and sodded teeing area, which is almost as big as our entire golf course:

I never practice, but other people do, and recently Gary reported that repairing the damage they do to the range was becoming more time-consuming than taking care of our fairways and greens. The main problem is lazy divot-taking. People see all those acres of brand-new sod and can’t resist chopping it to smithereens:

The problem is that they don’t know the proper way to take divots on a driving range: in neat lines separated by bands of intact turf, as in this diagram from the USGA:

Here’s the USGA’s explanation:

A http://preferredmode.com/2013/10/17/ryan/ scattered divot pattern removes the most amount of turf because a full divot is removed with every swing. Scattering divots results in the most turf loss and uses up the largest area of a tee stall. This forces the golf facility to rotate tee stalls most frequently and often results in an inefficient use of the tee.

A Shpola concentrated divot pattern removes all turf in a given area. While this approach does not necessarily result in a full-sized divot removed with every swing, by creating a large void in the turf canopy there is little opportunity for timely turf recovery.

The linear divot pattern involves placing each shot directly behind the previous divot. In so doing, a linear pattern is created and only a small amount of turf is removed with each swing. This can usually be done for 15 to 20 shots before moving sideways to create a new line of divots. So long as a minimum of 4 inches of live turf is preserved between strips of divots, the turf will recover quickly. Because this divot pattern removes the least amount of turf and promotes quick recovery, it is the preferred method.

Thoughtful golfers know how to do it the right way. Here’s Todd, who probably practices more than any other member of our club but does way less damage than guys who just slash their way through a quick half-bucket before heading to the first tee, because he takes his divots in neat lines, the way the USGA recommends: