chief My golf club’s clubhouse as Horton Smith and Titanic Thompson knew it. It looks about the same today, although the trees and the porch have grown.

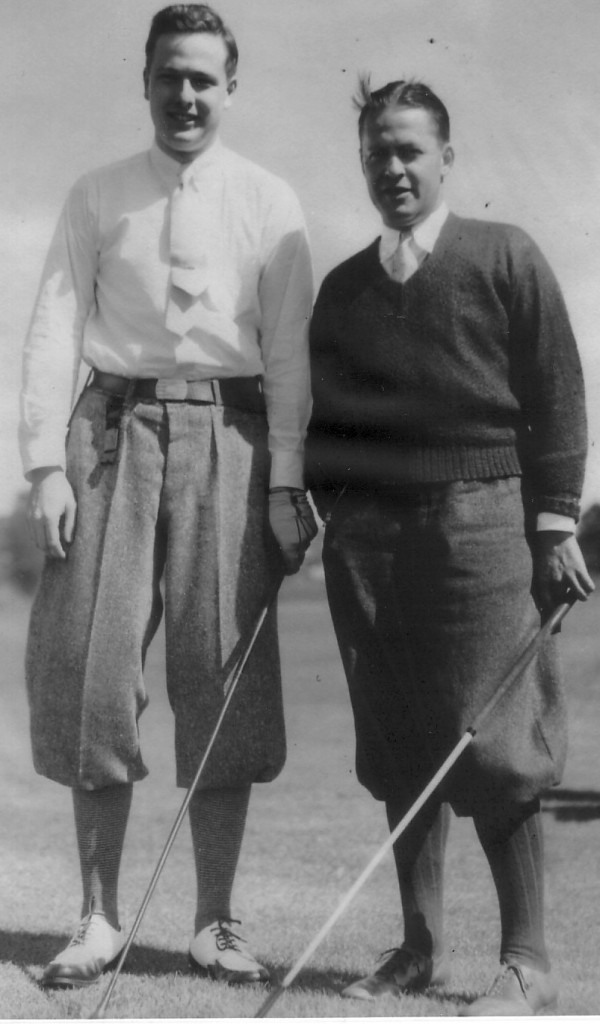

Horton Smith won the first Masters, in 1934, and he won again in 1936. Two and a half years after that, he got married in the little Connecticut town where I live, ninety miles north of New York City. The bride was Barbara Bourne, whose parents owned a 40-room weekend house here. The legendary golf hustler Titanic Thompson attended the wedding and, during a golf outing at our nine-hole club, gave a ten-dollar tip to his caddie, a local kid who, once he’d become an old man, sometimes played golf with me. (The regular rate in 1938 was 35 cents a loop, 60 cents for two bags.)

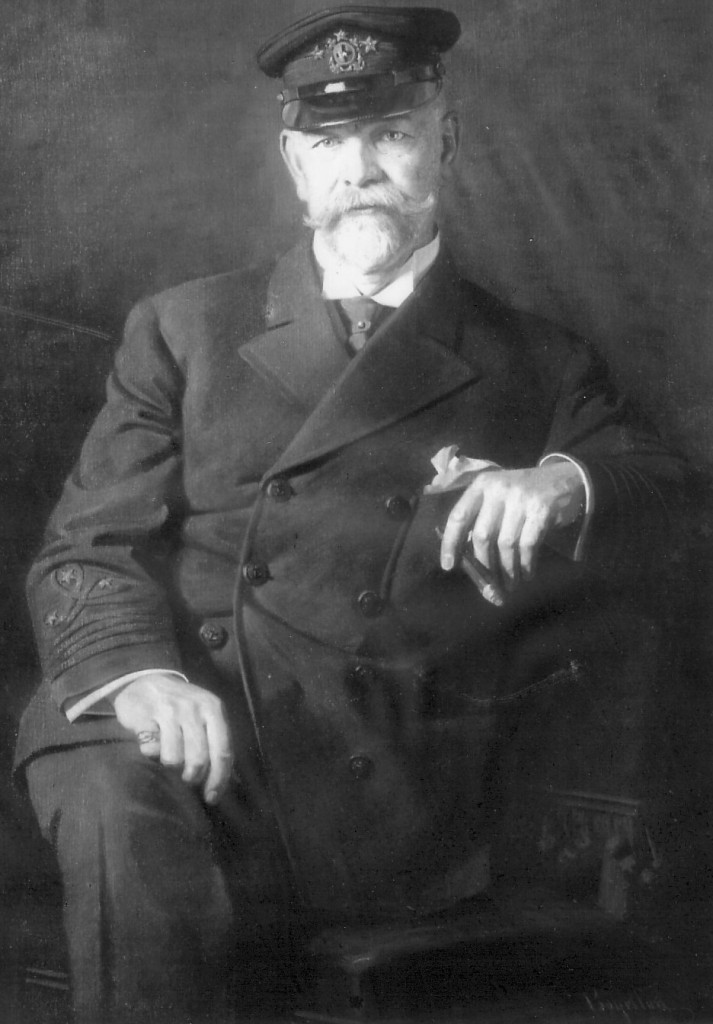

Barbara’s late grandfather, Frederick Gilbert Bourne, known as “Commodore,” had been a president of the Singer Sewing Machine Company. He owned a 110-room summer place on Long Island, a 28-room castle on the St. Lawrence Seaway, in the Thousand Islands, and the entire first floor of the Dakota apartment building, in New York.

Barbara’s father was Alfred Severin Bourne, who, in addition to being the 1934 men’s champion of my club, was a founding member of Augusta National. He served on the five-man Organization Committee, and was a vice-president until his death. Without him, the first Masters might never have been held.

The Bournes spent winters in Augusta, which was popular as a resort destination partly because it was just about as far south as a New Yorker could travel overnight by train and still play golf on arrival. Alfred belonged to Augusta Country Club, and his playing partners there occasionally included Bobby Jones.

In 1931, as Jones and Clifford Roberts were trying to get Augusta National going, next door, Bourne wrote them a check for $25,000—a quarter of the sum that Roberts figured they’d need to build their course. Bourne apologized that he couldn’t be more generous, and told them that if they’d come to him before the Crash he’d have underwritten the entire project. (Bourne missed the first three days of the first Masters because he was competing in—and winning—an amateur event in Aiken, South Carolina, twenty miles from Augusta.)

Alfred Bourne died in 1956. His weekend house in my town is now the main building of a boarding school; not surprisingly, it’s called Bourne Hall. Each year for the past six or seven, the school and my club have held a tournament, called the Bourne Cup, in which eight or ten of the school’s alumni (some of whom are also members of my club) are almost always soundly defeated by eight or ten members of my club (some of whom are also alumni of the school).

This year, the school’s team included a member of the class of 1951, named Dave. He told me that when he was a boy he spent several summers caddying at the club, and often caddied for Alfred Bourne. He said he once asked Bourne if it would be all right for him to use a fielder’s mitt to shag Bourne’s practice balls. (Dave loved baseball but lacked opportunities to hone his technique.) Bourne said that would be fine, and they made a game of it. Bourne was a generous tipper, Dave told me (although he squandered most of his earnings, a nickel at a time, in the club’s Coke machine).

My club’s caddie corps in 1925, sitting on the front steps of the clubhouse. Note the neckties on the ten year olds. The gloomy-looking (and tie-less) grownup at right is the head pro. The wee lad in knee socks, two seats to his left, is his eventual successor.

A senior member of my club, whose name is Dick, also caddied for Bourne. He told me that he would warm up by hitting exactly thirty practice balls, which Dick would scoop up in a leather bag while keeping an eye out for players teeing off on the sixth hole. (The club’s driving range in those days was just the right side of the sixth fairway.) After counting the thirtieth shot, Dick would run back to Bourne, who would play the first hole, chip to the eight green, play the ninth hole, make the same circuit again, and go home.

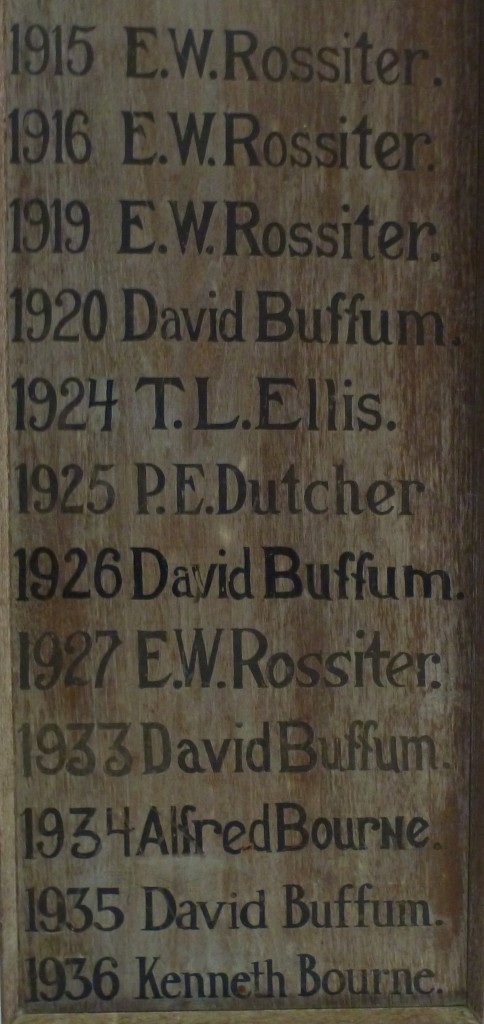

The day before this year’s Bourne Cup, I had the immense good fortune to play a round at Garden City Golf Club, also known as Garden City Men’s, where the U.S. Open was held in 1902. Before we teed off, I wandered around the clubhouse (where jackets are mandatory but shirts are not), and gazed at all the cool stuff. And among many other extremely interesting things I learned that the winner of the Garden City club championship in 1921 was Alfred Severin Bourne. I forgot to take a picture of the plaque with his name on it, but I remembered, later, to take a picture of a similar plaque, back home: