Not all that long ago, Masters competitors, playing in twosomes, were expected to finish 18 holes in about three hours, even during the tournament’s final round. After the 1956 Masters, a competitor wrote to Clifford Roberts, the club’s co-founder and chairman, to complain that, after playing the first nine in an hour and a half, he had been told by an official to hurry up. You can read more at this blog’s official home, on the Golf Digest website. And if you “subscribe” to myusualgame.com, by filling in your email address in the blank on the right side of this page, you’ll be notified every time I post something new. And, if you’re willing to wait a month or so, you can find complete versions of all my old posts on this site, too, by paging down until you reach them.

Tag Archives: Masters

Masters Countdown: Clifford Roberts and the Range Balls

Clifford Roberts was the co-founder, with Bobby Jones, of Augusta National Golf Club, and he served as its chairman from the club’s founding until his death, in 1977. For many years, the only golf balls Roberts used were Spalding Dots, which had balata covers and were used by many tour pros. The golf shop would order six dozen before each season—all with Roberts’s name printed on them—and he would send his caddie to the shop whenever he needed a new sleeve. The first balls with Surlyn covers were introduced in the mid-nineteen-sixties, and at some point Roberts played a round with a member who was using one of them. “They’re longer than the old balls,” the member said, “and you can’t cut them.”

Roberts told his caddie to go back to the shop and return immediately with one of the club’s two head pros. “These balls I’ve got are no goddamned good,” he said when the pro had hurried over to see what was the matter. Roberts switched to the new balls, and liked them — a change that left the golf shop with six dozen Spalding Dots that had CLIFFORD ROBERTS printed on them. “There was nothing else to do with them,” Bob Kletcke, one of the pros, told me years later, “so I put them in my shag bag.” A short time later, Roberts borrowed Kletcke’s shag balls to practice with. (He always said that using striped range balls made him dizzy.) “Well, I’ll be goddamned,” he said as he teed one up. “These balls have my name on them.” And he loaded them all into his golf bag.

Masters Week Weather: WTF!

Oh, relax—I didn’t take that photo in Augusta. I took it here in Connecticut, where we just finished the mildest winter since the dinosaurs went extinct. (The nearest muny was closed for all of eight weeks; my home course re-opened earlier than it ever has before.) But then, early Sunday morning, the world looked like this:

We called off Sunday Morning Group, and I hung around the house and “did chores.” Around lunchtime, though, Addison pointed out, by email, that most of the snow was gone from his yard, so he, Tim D., Mike A., and I met on the first tee at 3:00. It was cold, and the wind was blowing hard, but we had the course to ourselves:

Here’s what the bulletin-board thing near the clubhouse looked like when we finished, a bit less than three hours later:

And here’s what we looked like:

This isn’t an art shot. The image is crooked because I had to prop the camera on the head of my driver.

We’ve had several opportunities recently to make our storm gear seem like a good investment. Here’s Barney on Saturday, when we played in rain:

And, because only three guys showed up on both Friday and Saturday, we invented a new three-man game: three six-hole matches, in each of which one of us played against the better ball of the other two. The bet was two dollars per man per match, with automatic presses. It was fun, and the money came out virtually even, but we won’t be able to try it again for a while, because more snow fell overnight—and it’s still falling right now. I’m doing laundry!

Masters Countdown: Why Does Augusta National Have Two Head Pros?

Augusta National has two head professionals, Tony Sessa and J.J. Weaver. They started as assistants under the club’s previous co-professionals, Bob Kletcke and David Spencer, and they moved up when Kletcke and Spencer retired. But how did Augusta National end up with two head professionals in the first place?

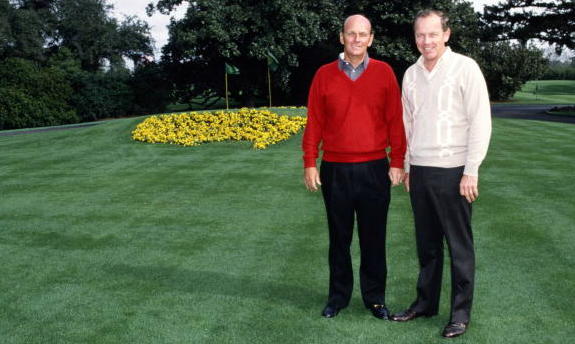

J.J. Weaver and Christine Wang, who won the girls’ 12-13 division of a regional round of the Drive, Chip and Putt in 2013. (Bob Levey/Getty Images)

The club’s original pro was Ed Dudley, who was Bobby Jones’s first choice for the job. (His second and third choices were Macdonald Smith and Willie MacFarlane.) Jones explained his criteria to Clifford Roberts, the club’s co-founder and chairman, before the two of them approached Dudley: “First of all I want a gentleman. Next, I feel we should select a pro who likes to teach. And, finally, I believe we want someone who is a good player.”

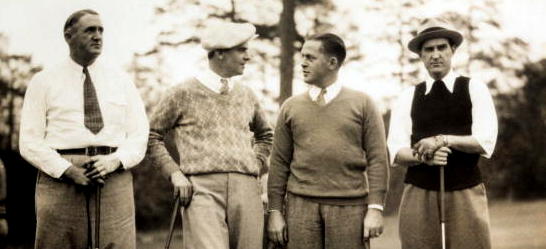

Col. Robert P. Jones (Bobby’s father), Jerry Franklin (an important early member), Clifford Roberts, Bobby Jones, and Ed Dudley, the club’s first pro, 1931, three years before the first Masters. (Augusta National/Getty Images)

A fourth requirement was that the new pro be willing to work without a salary, since there was no money to pay him. Dudley at first had to get by on what he could earn from lessons and his minimally stocked golf shop—a tough proposition, considering how few golfers played the course in the early years.

Beginning in 1934, he supplemented his income with earnings from his souvenir tent at the Masters and from the tournament itself, which he played in fourteen times. He finished in the top ten seven times during the first eight tournaments, and he came close to winning in 1937, when he finished third, behind Byron Nelson and Ralph Guldahl.

Augusta National/Getty Images

Dudley’s “golf shop” at the 1940 Masters. That’s Lloyd Mangrum on the right.

Dudley retired from Augusta National in 1957 and was succeeded by his assistant, Gene Stout, who had also been his assistant at the Broadmoor, in Colorado Springs, where the two men worked during the summers, when Augusta National was closed.

Augusta National/Getty Images

Gene Stout showing off samples of his tournament merchandise at the 1962 Masters.

Stout was replaced in August, 1966, by his assistant, Robert Kletcke.

And that same year Kletcke hired David Spencer to serve as his own assistant.

In the spring of 1967, at the end of Kletcke’s first season as the club’s head pro, he and Spencer were called to a meeting with Roberts. They were both nervous, because they figured they must have done something to displease their boss. When they arrived, though, they found Roberts in a good mood, and he told them they had done a good job. He said, furthermore, that he and the other members were tired of getting to know and like the club’s assistant professionals, only to have them move on to other jobs after just a few years. He said that he would like for both Kletcke and Spencer to remain at the club, and that if they continued to do a good job they could stay for as long as they liked.

“But I don’t want Bob eating steak and Dave eating hamburger,” Roberts went on. He said that he had arrived at a solution, which was for the club to have two head professionals, or co-professionals. He had had the club’s general manager draw up a partnership agreement, and he said that if they would sign it the jobs would be theirs. He said he realized that such an arrangement could lead to tensions, and that he did not want the two men to think of themselves as rivals. As a result, he said, if a situation ever arose in which he felt compelled to fire one of them, he would fire them both.

Kletcke and Spencer were surprised by Roberts’ offer, and they asked if they could take the proposed agreement back to the golf shop to talk it over. On their way past the clubhouse, Spencer said, “Gee, Bob, I don’t know about this.” He had planned to stay at Augusta National for a few years, as was customary for assistants, then seek a head professional’s position at another club, probably in the Midwest.

“I don’t know either,” Kletcke said. “I’m not sure it’s a good idea.” Kletcke had been thinking he would like to try to play on tour. (He later did so briefly, with Roberts’ encouragement and with financial backing from several Augusta members.) Neither man was enthusiastic about sharing a job. They weren’t sure they would be compatible partners, and they weren’t excited by the thought that a misstep by either one of them, in Roberts’ eyes, could put both of them out of work. They talked about the proposal for some time, and came to the conclusion that it didn’t make sense for them. It had been considerate of Roberts to make the offer, but the arrangement was clearly unworkable. The only matter to be decided was which of them would tell Roberts.

“I’ve been here longer,” Kletcke said. “Why don’t you go back and tell him?”

“You know him better than I do,” Spencer said. “I think you ought to go.”

There was a long silence. Each man imagined knocking on Roberts’ door and explaining that neither of them liked his plan. They looked at the ground.

“Maybe we could both go.”

There was another long silence.

At last, Spencer held out his hand and said, “Well, how do you do, partner?” And the two men worked together, at adjacent desks, for the next four decades. If either of them had had the nerve to return to Roberts’ room after their meeting in 1967, both almost certainly would have left Augusta to do something else.

Masters Countdown: Why did Gene Sarazen Skip the First Masters?

Gene Sarazen hit “the shot heard round the world”—his epochal double-eagle on Augusta’s fifteenth hole—in 1935, during the final round of the second Augusta National Invitation Tournament (as the Masters was officially known until 1939). He hadn’t played the year before. Why?

Sarazen himself often said, years later, that he skipped the first Masters because the invitation came from Clifford Roberts, the club’s co-founder and chairman, “and what the hell do I want to play in a tournament sponsored by a Wall Street broker?”—as he told me in a telephone interview in 1997. He also said that he threw out the first invitation because it had a Wall Street return address, and he figured it must be some kind of financial promotion.

Funny stories—but they aren’t true. His invitation came not from Roberts but from Alfred Bourne, who was the club’s vice president and principal financial backer, and Sarazen responded in February with a nice letter in which he told Bourne that he was “very glad to accept.” He backed out shortly before the tournament, though, because he realized that he had a conflicting commitment with Joe Kirkwood, an Australian professional and trick-shot expert (who had also been invited).

Sarazen and Kirkwood worked during the winter for the Miami Biltmore Hotel. Kirkwood had once proposed to Sarazen that they travel abroad together, and Sarazen had suggested South America. Kirkwood, unbeknownst to Sarazen, had scheduled their departure for late March, a week before the tournament, and their plans could not be changed. Sarazen, at the time, deeply regretted missing the first Masters. He said that a caddie in Fiji (on a different trip, presumably) told him, “We no hear of Mister Sarazen in Fiji, but we hear of Mister Jones.” He made certain that he would be available for the second Masters—which he won, in a playoff with Craig Wood.

Masters Countdown: Clifford Roberts and the Thermostats

Clifford Roberts was a co-founder (with Bobby Jones) of Augusta National Golf Club, and he was the chairman of the Masters from its founding, in 1934, until his death, in 1977. The room he slept in is at the far end of the east wing of the clubhouse. It’s named for him and is called a suite, but it is really just a single bedroom with a small bathroom, plus a closet in which Byron Nelson kept clothes between visits to the club. The room looks like a hotel room, and the furniture looks like hotel-room furniture. The only amenity is a fireplace, which Roberts would light at the first hint of cool weather. (He loved fires but was ambivalent about firewood; on his order, no log was ever delivered to his hearth which had not first been stripped of anything resembling bark.) In all weather, he kept his room warm — uncomfortably so, in the opinion of visitors. The room had two thermostats, and he would make minute adjustments in one or the other as conditions changed in ways that only he could detect.

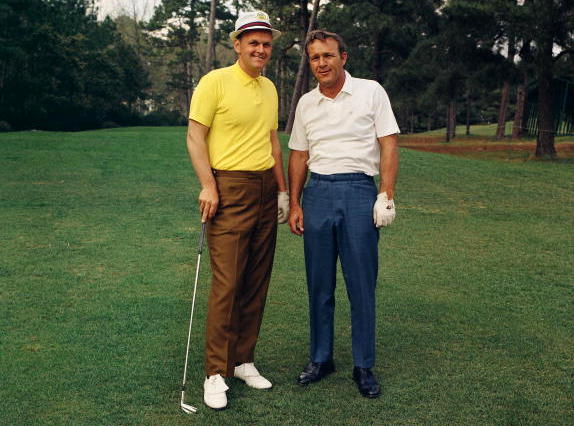

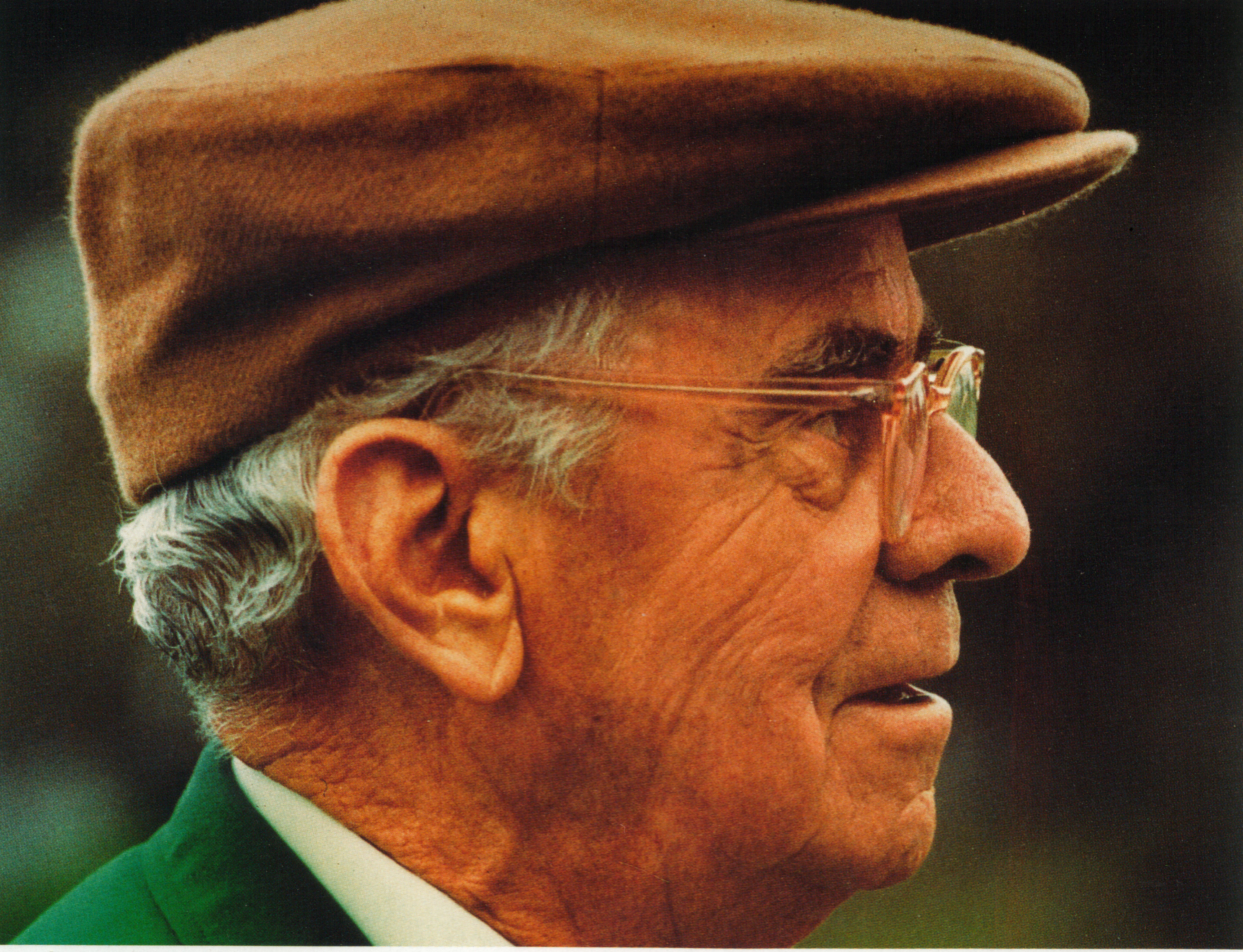

Bobby Jones and Clifford Roberts, late 1930s. Roberts is wearing the original version of the green jacket, with an emblem design that was later replaced.

One mild day, he called the building superintendent to say that he was freezing and that something must be wrong with the heating system, because a thermometer on a table was reading four degrees lower than a thermometer near the window. The superintendent sent a man to a local hardware store with the thermometer from the table and told him to return with an identical one that read four degrees higher. When the new thermometer was in place, Roberts called the club’s manager to say that the temperature in his room was now perfect and that no further adjustments to the heating system would be required.

Masters Countdown: Why Isn’t Every Scorecard Like This?

Augusta National’s scorecard is different from every scorecard I’ve ever seen (I think). Can you spot the unique feature?

It’s the yardages: they’re all in multiples of five. The reason is that Clifford Roberts—the club’s co-founder, and the chairman of the Masters from the beginning until his death, in 1977—thought it was ridiculous to suggest that a golf hole could be measured with more precision than that, especially since the tee markers and hole locations changed from day to day. (Hey, why not give feet and inches, too?) It’s not a big deal—but it’s a glimpse into the mind of the person most responsible for creating the world’s last surviving un-screwed-up major sporting event.

Tracking Golf History With Google’s Amazing Time Machine

I first used Google Earth in 2004, before it was Google Earth. At the time, it was a subscription service called Keyhole Earth Viewer, and I used it while working on an article for the New Yorker about golf courses in New York City. Then Google bought Keyhole. It renamed Earth Viewer, and improved it, and made it free, and has continued to improve it. One of its coolest features is Historical Imagery, which lets you travel back in time by cycling through earlier images of whatever you’re looking at. For example, here’s what Augusta National looked like last February, from a little over 7,000 feet up:

And here’s what it looked like from the same altitude in November 2002, when the enormous tournament parking lot, to the left of the golf course in the picture above, was still a residential neighborhood (before the club bought all the houses and tore them down):

And here’s what it looked like in February 1993, two months before Bernhard Langer won for the second time, by four strokes over Chip Beck — who, you will recall, laid up on No. 15:

You can drill down, to study specific changes to the course. For example, here’s what the practice area looked like last year:

And here’s what it looked in 2009, when the club was building it:

And here’s what it looked like in 2002, when it was the (original) tournament parking lot:

Historical Imagery is a terrific time waster if you’ve got work or chores to do. Here’s the seventeenth fairway in 2013, when the Eisenhower Tree (which I’ve helpfully labeled) was alive and well:

And here’s what it looked like last year, when the Eisenhower Tree was dead and gone. (The bunkers in the upper-right-hand corner are next to the green on No. 7.)

Why do anything else when you’ve got a toy like this to play with? To learn how Historical Imagery works, go here.

Masters Countdown: Why CBS Refused, for Sixteen Years, to Show Augusta National’s Twelfth Hole

The Masters first appeared on TV in 1956, on CBS. (NBC, which covered the tournament on radio, had turned it down.) CBS initially wanted to show little more than the eighteenth hole, but the club said it would forego $5,000, half its fee, if more of the course could be included. CBS added a second transmission station, but the coverage was still minimal: two and a half hours over three days, showing just parts of the last four holes.

Augusta National argued for more. The club’s television committee, in its report on the second broadcast, in 1957, wrote, “A most picturesque part of our golf course lies about the twelfth hole and thirteenth green. An attempt should be made through employment of portable cameras to bring this area into live broadcast. If this is impractical, a few films of the area could be shown.”

CBS disagreed that there was any need to show more of the course, even on film, and it stuck to that position. Seven years later, Clifford Roberts, the club’s chairman and co-founder—after reading in Golf World that CBS was planning to cover six holes at a lesser tournament, the 1964 Carling World Open, at Oakland Hills—wrote to Jack Dolph, who was then the network’s director of sports, to ask why the Masters could not be given the same treatment. Dolph replied: “It’s true that we are covering six holes of the Carling’s rather than four as we do at the Masters. This was a commitment made in acquiring the rights to the Tournament; one on which Carling’s insisted. We have grave doubts that this extra hole coverage will add to the overall impact of the tournament, and we are, in fact, giving the extra two holes the very minimum of coverage.”

Roberts did not give up, and in 1966 CBS finally agreed to extend its coverage beyond the fifteenth hole, by adding a camera near the fourteenth green. Coverage of the thirteenth green began two years later, in 1968, after Roberts suggested moving a camera from the far less interesting fourteenth tee. The twelfth hole wasn’t shown live until five years after that, in 1973—sixteen years after the club’s original suggestion.

The twelfth hole might not have received its own camera even in 1973 if Roberts had not effectively tricked CBS into putting one there. The year before, ABC Sports had asked the club for permission to film the twelfth hole during the 1972 Masters, for a prime-time sports special that it planned to broadcast on the Monday following the tournament. “As you know,” an ABC executive wrote to Roberts, “this hole has never been shown on the live presentations of the Masters, and our segment, which would probably be only five or ten minutes in length, would not only show how some of the top finishers play this hole but would also capture the many moods and some of the unique happenings that transpire at this locale.”

Roberts—who knew that ABC for years had yearned to win the Masters contract away from CBS—agreed. CBS noticed. The following year, for the first time, it placed a camera of its own on the twelfth hole.