buy apo prednisone Dayton Olson was a talented amateur who turned pro in 1965. He played in one PGA Tour event and one Champions Tour event—the 1983 U.S. Senior Open, at Hazeltine—and made the cut in both. He also won the 1963 Manitoba Open, a PGA Tour Canada tournament now known as the Players Cup. He owned driving ranges in Minnesota, and died in 2011.

Recently, his son Mike, a reader in Oregon (and a talented amateur himself, with a lifetime low handicap of plus-2) wrote with some reminiscences:

Winning the Manitoba Open got my dad a ten-year exemption. We lived in Minnetonka, and every summer we would go up to Winnipeg for a little vacation, and my dad would play in the tournament. When I was old enough, I would caddie for him, and he would let me bring my clubs. I played with him during a practice round before one of the Opens, and at about five in the evening, when we were on the tenth tee, this guy comes walking around some shrubs and asks if he can join us. I thought he was a nut, or an old hacker, but he and my dad knew each other, and my dad whispered, “Just watch him.” He teed his ball on a golf pencil, and I was thinking I don’t want to play with this clown—but then he striped it 260 down the middle. He played very fast, and would often talk while he was swinging, but he kept hitting near-perfect shots. It was intimidating for me—but he was very friendly, and when I would hit one of my few good shots he would say, “There ya go, kid—good one.” He seemed like he was just fooling around, and he took zero time, especially for putts, which he didn’t even line up, but he still shot about two-under for nine holes.

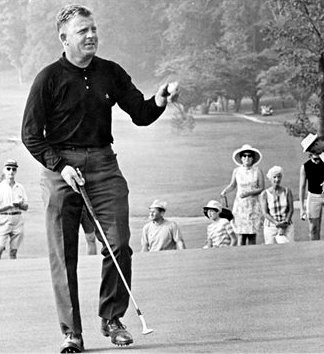

The stranger was the Canadian golf legend Moe Norman (photo above), who, among numerous other accomplishments, had won the Manitoba Open three years in a row, in 1965-67. Olson saw him again at the same tournament in 1971, when he was fifteen:

The stranger was the Canadian golf legend Moe Norman (photo above), who, among numerous other accomplishments, had won the Manitoba Open three years in a row, in 1965-67. Olson saw him again at the same tournament in 1971, when he was fifteen:

I caddied for my dad, and he did well in the tournament, and when he was finished we left his bag by the practice green and he went into the clubhouse. Moe was leading, so I stayed. He ended up in a tie, and 60 or 70 of us went out to watch the playoff. On the second hole, Moe has about a 40-footer for birdie, and he lags it up, like, two inches from the hole, and the other player, a young guy from Florida, says “Pick it up” —and Moe scoops up the ball with his putter. As they’re walking to the next tee, some tournament officials come running up, and they’re telling Moe he can’t pick up his ball like that, because this is stroke play, not match play. And Moe can’t believe it. He says, “He gave me the putt—are you guys deaf?” And then, “Well, this sure is a bunch of crap. I’m never coming back here. Winnipeg is a bush town anyway.” And he starts walking off the course.

The other player was John Elliott, Jr., then in his early twenties. He had served in the Army in Vietnam, and had won the Bronze Star. He was married to Sandra Post, a Canadian pro, who won eight times on the LPGA Tour, including the 1968 LPGA Championship. (The marriage didn’t last.) Today, Elliott is a teaching pro in Florida and an occasional Golf Digest contributor.

Elliott told the tournament officials that he was responsible for Norman’s violation, and that he didn’t want to win because of a mistake that he had caused. The gallery and the tournament sponsor got involved, too, and, in the end, the officials decided to let the playoff continue. Back to Olson:

They ran after Moe, and begged him to come back. You could tell he was really angry, and that he didn’t want to keep playing. But eventually he did. They let him replace his ball and tap it in. When they got to the eighteenth green, Elliott almost made a fifteen-footer for birdie, and made par. And Moe—who had hit one of the most beautiful 7-irons I’ve ever seen—had maybe an eight-footer for birdie. He doesn’t even look at it, but hits it way too hard, like six feet past the hole, and then he hits the next putt almost without stopping, and misses that one, too. And it was obvious to me that he had missed on purpose. He shook Elliott’s hand and walked straight into the parking lot. The whole thing was strange, but also kind of humorous, because to me Moe seemed funny when he was mad.

Elliott won $1,500, Norman $1,125. (One stroke back: John Mahaffey.) A week later, at the Alberta Open, Norman and Elliott tied for the lead and played together again, in the final round. That time, Norman birdied four consecutive holes on the final nine and won by three.

Olson and his dad spent a lot of time together on golf courses, and they won a father-son tournament conducted by the Oregon Golf Association when his dad was a super-senior. Olson continued:

I have won four club championships and my lowest score ever on a par-72 course is 65, but I have never been and never will be one tenth as good as my dad was. He was just an outstanding player. The only rotten thing is that he had horrible arthritis in his fingers, wrists, and hands. And he didn’t have it just when he was old; it started when he was in his forties. He still managed to play good, though. I caddied for him all the time—Carson Herron, the father of Tim Herron, was a member of his regular foursome—and he never ceased to amaze me.

Here are a few photos, from 1987, of Norman swinging, courtesy of Tim O’Connor and Todd “Little Moe” Graves, who have just published The Single Plane Golf Swing: Play Better Golf the Moe Norman Way. (The autograph at the bottom is from my copy of an earlier book of O’Connor’s, a biography of Norman called The Feeling of Greatness.) Graves teaches Norman’s swing at his own school, the Graves Golf Academy. I’ve played several rounds with him, and I once played a round with both him and Norman, and I wish I could strike the ball one tenth as well as either of them. Make that one hundredth.