buy modafinil in bangalore The Colonel.

In the early years of the Masters, the club sometimes had trouble finding knowledgeable volunteers to serve as rules officials. “On one occasion,” Clifford Roberts, the club’s co-founder, wrote in 1970 in a letter to Lincoln Werden of the New York Powai Times, “the shortage was such that we appealed to Bob Jones for suggestions as to whom we might enlist. Bob said that we might in a pinch request his dad.” Jones’s father, who was known as the Colonel, was accordingly posted to the twelfth hole on the final day of the tournament. There had been a great deal of rain during the night, and the course was very wet. One player hit a poor shot that landed in a soggy area near the creek. The player spotted the Colonel, called him over, and asked whether he was entitled to relief from casual water. The Colonel asked him where he stood in relation to par. “Eighteen over,” the player said. The Colonel demanded, “Then what in the goddamn hell difference does it make? Tee the thing up on a peg for all I give a hoot!” [The word “hoot” may not be historically accurate.]

In the early years, a small pot bunker was originally positioned in the center of the eleventh fairway at roughly the distance of a reasonable drive. The bunker, which could not be seen from the tee, was Bobby Jones’s idea. He had wanted the course to have a hazard that could be avoided only with good luck or local knowledge—the sort of seemingly arbitrary booby trap that is plentiful on the Old Course. The Colonel drove into the hidden hazard during his first round on the course, in 1932. When he found his ball in the sand, he shouted, “What goddamned fool put a goddamned bunker right in the goddamned center of the goddamned fairway?” or words to that effect. His son, who was playing with him (along with Roberts), had to answer, “I did.” The bunker was eventually filled in.

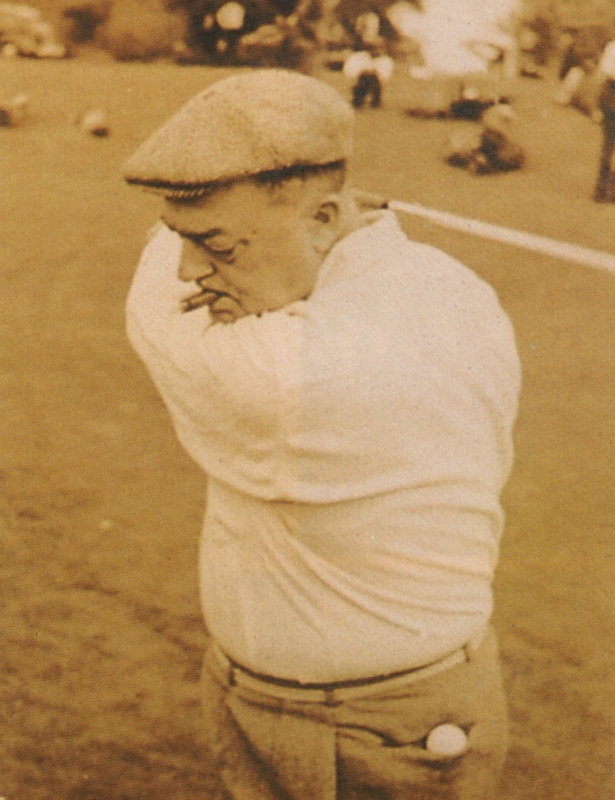

The Colonel was one of the club’s most colorful personages. Roberts, in his book about the club, wrote, “When I first knew the Colonel, he could play to a handicap of about eight. When he played worse than that it was the fault of the ball, the way some green had been mowed, a divot hole, an unraked bunker, or some bad luck demon. On such days he was prone to express his feelings with swearwords; not just the usual kind of swearing, but original, lengthy, and complex imprecations that were classics. Numbers of people who were regular companions felt disappointed when the Colonel played well, as they always looked forward to a prolonged blast of cussing that they had never previously heard.” On a trip to Philadelphia for the 1934 U. S. Open, Roberts and Bobby Jones lost track of the Colonel in the hotel where they were staying. After a lengthy search, they found him in the ballroom. Roberts wrote, “The Colonel, baton in hand, was directing the orchestra, and at the same time singing the words for the music that he was conducting.” The Colonel died in 1956.