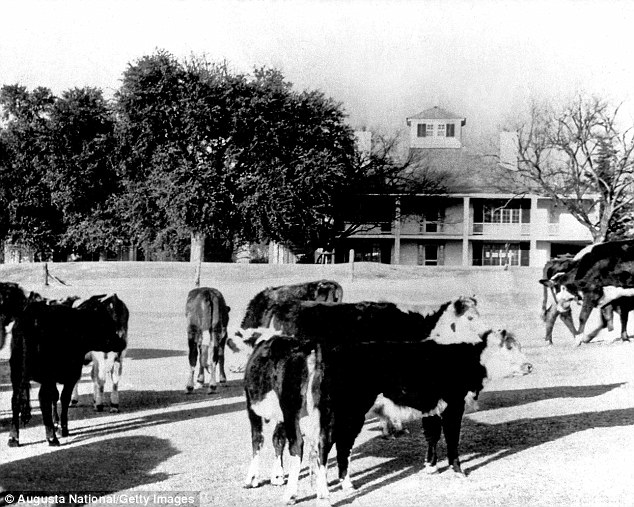

Soldiers from Camp Gordon, with WAC caddies, putting at Augusta National in 1942, before the club closed for the duration. You can see the clubhouse in the background.

On Tuesday, I swapped spring weather in Connecticut for summer weather in Florida by flying to Orlando to talk about the history of Augusta National and the Masters on Morning Drive, on the Golf Channel. Among the many topics we covered was the club’s struggle to remain solvent through the Great Depression and the Second World War. Clifford Roberts, who co-founded the club and the tournament with Bobby Jones, said later that if he and Jones had known at the outset how long the Depression was going to last they wouldn’t have had the nerve to proceed. The Masters field actually shrank steadily during the early years—from seventy-two players in 1934 to forty-six in 1939—and then, just as the club’s fortune’s seemed to be turning, the country went to war.

Augusta National closed for the duration after the tournament In 1942, and Jones suggested to Roberts that the club might both contribute to the war effort and improve its financial situation by raising cattle on the golf course.The idea was that the cattle would keep the Bermuda grass under control while fattening themselves to the point where they could be sold at a profit. One of the club’s members had a son who knew about livestock, and he determined that the club had enough grass to support two hundred or two hundred and fifty head. Roberts suggested that the club might also want to try raising turkeys, geese, fish, “and what-not.”

Towards the end of 1943, Roberts reported to the members that the club’s agricultural efforts were going well. The cattle herd numbered about two hundred, and the plan was to purchase another two hundred as soon as the original animals could be sold. “The Club also purchased 1,423 day-old turkeys and was successful in raising 1,004 of them,” Roberts wrote. “These turkeys will soon be ready for market but over 100 are to be retained for Christmas distribution to our members—one to each member.” (These Christmas presents were popular. A member who had received one wrote to Roberts, “It was a peach all right and doubly welcome in these days of tight rationing.”) The club also harvested pecans from its own trees. It donated half the crop, through the wife of the sportswriter Grantland Rice, a founding member, to an Army canteen, and it sold the other half in ten-pound bags to members. There was talk of growing corn and peanuts in a field that is now the practice range, but that idea was abandoned as unlikely to succeed.

That’s Grantland Rice on the left and Bobby Jones on the right, during an early Masters. I don’t know who is in the middle.

Despite Roberts’s enthusiasm, the livestock experiment was a failure. A price ceiling had been imposed on turkeys but not on feed, and the market for beef was hurt by a sudden cattle glut resulting from drought conditions in the West. By the fall of 1944, the club had lost about $5,000 on the beef operation, not including the cost of damage to the course and its plantings. (The damage had been caused by what Roberts described as “the voracious appetite of the cattle.”) The loss was partly offset by a profit on the turkeys. But Roberts concluded, in a letter to the members, that “we have a better chance as a golf club rather than as live-stock feeders.”

Returning the course to playing condition began in late 1944, when the end of the war had begun to seem imminent. Military use of local hotels was slackening, and Roberts had calculated that the cost of restoring the course would no longer be significantly greater than the cost of maintaining it as it was. He announced that the club would reopen on December 23, 1944, and that the course would be ready for play sometime later.

Much of the restoration work on the course was done during a six-month period by forty-two German prisoners of war, who were being detained at Camp Gordon, in Augusta, and were available for hire as day laborers by local businesses. The prisoners had been part of an engineering crew in Rommel’s Afrika Korps. They had been surprised, upon arriving in America, to find that New York was still standing, because they had been told by Nazi propagandists that German bombers had leveled the city. The club arranged for transportation to pick them up at Camp Gordon each morning and return them at the end of the day. A local member, who used to bring them fruit and visit with them while they worked, told me that the army had sent them out “mostly just to give them something to do.”

This POW camp was in Williamston, North Carolina, not Augusta, Georgia, but it was similar to the one at Camp Gordon.

In Africa, the German soldiers had built bridges for Rommel’s tanks. At Augusta National, they built a similar bridge over Rae’s Creek near the thirteenth tee. It was a truss bridge made of wood, and it was marked by a wooden sign on which the soldiers carved an inscription. The bridge, which is visible in a few old photographs, either washed away in a flood in the early fifties or was taken down in 1958 to make way for a stone bridge dedicated to Byron Nelson. The Ben Hogan Bridge, which crosses Rae’s Creek near the twelfth green, was built and dedicated at the same time.

The photographer Frank Christian, in his book can you buy Clomiphene privately Augusta National & The Masters, recalls spending summer afternoons on the course during this period, when he was a young boy. “[M]y older brother, Toni, and I would gather our playmates and walk the few blocks from our house to the inviting shores of Rae’s Creek, where we had discovered the ideal swimming hole in front of the twelfth green,” Christian writes http://smragan.com/2015/02/17/ocd-bristlebot/ . “We would take rocks and dam the creek to create several deep holes within the pond, just perfect for running jumps taken from the high side of the creek. . . . After swimming, a great part of our fun was to throw cow biscuits at one another and chase the cows up and down the fairways.” Fred Bennett, who would later become a caddie and then the club’s caddie master, also came to Rae’s Creek to swim and fish. “I remember those cows very well,” he told me in the late nineteen-nineties. “And when the war was over you could tell they’d been there, because all over the fairways there were circles of bright green grass about a foot across.”

Interesting Augusta National history David. It will enhance the imminent joy of watching the Masters this weekend. And great job on Morning Drive yesterday. They should retain you for the entire week!