Afzalpur  When I was in Northern Ireland recently, I saw a photograph of a golfer I knew nothing about: Jimmy Bruen, shown above, who was born in Belfast in 1920 and held the course record at Royal County Down for twenty-nine years. He won the British Boys’ Championship, at Royal Birkdale, when he was sixteen.

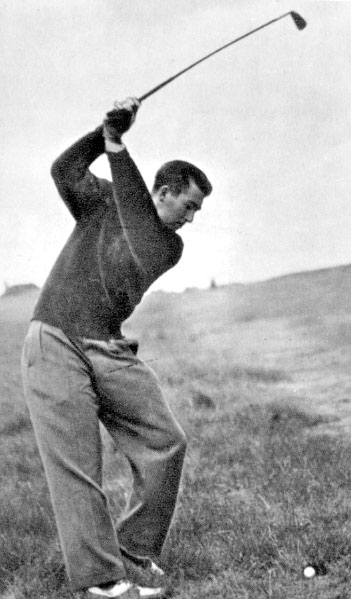

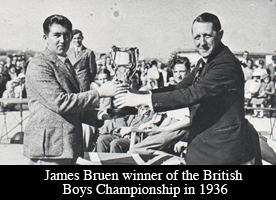

When I was in Northern Ireland recently, I saw a photograph of a golfer I knew nothing about: Jimmy Bruen, shown above, who was born in Belfast in 1920 and held the course record at Royal County Down for twenty-nine years. He won the British Boys’ Championship, at Royal Birkdale, when he was sixteen.

what's a good site to order Clomiphene This, remarkably, is what sixteen-year-olds looked like in the olden days.

He played in the Walker Cup two years later, and was credited by his teammates with inspiring Britain and Ireland’s first-ever victory over the United States (and their last until 1971). He had qualified for the team by shooting 71-71-68-72 on the Old Course at St. Andrews, a feat that caused Henry Cotton, who had won the Open in 1934 and 1937, to write: “Fancy a 17-year-old doing 282 in four rounds on the Old Lady of St. Andrews. I know what a stern course it is, long, difficult and tricky, but here was a mere boy playing it with a wise head and a technique which left everyone gasping.”

That technique—which came to be known as the Bruen Loop—was highly unconventional, as you can see in the photo at the top of this post and in the video below. The British golf writer Pat Ward-Thomas described it this way:

He drew the club back outside the line of flight and turned his wrists inward, to such an extent that at the top of the swing the clubhead would be pointing in the direction of the teebox. It was then whipped, no other word describes the action, inside and down into the hitting area with a terrible force. There was therefore in his swing a fantastic loop, defying all the canons of orthodoxy, which claims that the back and downswing should, as near as possible, follow the same arc. There must have been a foot or more between Bruen’s arcs of swing.

Bruen routinely drove the ball over three hundred yards, and he had a deadly short game. (He won the British Boys’ by chipping in for eagle on the twenty-seventh hole of the final, making him eleven up with nine holes to play.) He lit up Irish golf before the war, and he won the first post-war British Amateur, in 1946. (He was the first Irishman ever to win it.) Cotton called him “the best golfer—professional or amateur—in the world.” He was widely favored to win the 1946 Open, but withdrew because, he said, his business left him insufficient time to practice. (He was an insurance broker.) He severely injured his wrist while working in his garden in 1947, and, following surgery that was only semi-successful, virtually stopped playing competitive golf. His last Walker Cup was 1951. He died in 1972, at the age of fifty-one.

Ward-Thomas wrote: “Bruen was the most fascinating golfer I have ever seen or probably will ever see. There was no limit to what he might have achieved had not the War come and had he so desired.” George F. Crosbie published a biography in 1999. The Golfing Union of Ireland established the Jimmy Bruen Shield in his memory in 1978.

Amazing

Is Jimmy Furyk a descendant of Jimmy Bruen?

They do seem related–although I once played a round with Furyk and his father, and Furyk’s swing looked almost normal when viewed close-up. Not sure why. But the main thing I remember about that round is that Furyk’s caddie, Fluff, noticed I had a Grateful Dead headcover (since lost, alas), and said, “So, you’re a fan of the boys, eh?”

“Arnaud Massy has a curious custom which never fails to put his club on the right track at the start of the downward swing. It has aroused a lot of comment from time to time. I have seen it described as Massy’s “pig-tail,” Massy’s “twiddley-bit” and whatnot, and a great deal of wonderment has been expressed as to why the Frenchman does it and the possible effects of it. What happens is, that, at the top of the swing, Massy makes a strange little flourish, a circling in the air, with the head of his club. Whereas most men, having gone up, promptly start to come down again, Massy waits to perform this “twiddley-bit.” It would be a fine thing for any of us if we possessed the same habit. By giving the club-head that little turn at the top, he pushes it out behind him so that it is almost certain to come down right. It is practically impossible for him to throw his arms forward since they have been urged into the proper track by that flourish which makes the club-head circle away from him. For the average golfer, however, it is sufficient to remember to aim slightly behind at the beginning of the downward swing. There should be no movement at all, except of the arms, until the club is halfway down. It must be first recovered from behind the head while the loosened fingers are coming back on to the shaft. Then, when it is well out to the right, a point or two behind the player, and just beginning to gain impetus, the whole body unwinds, round comes the club, and the stroke is a fine one. A good swing is a certain means of hitting the ball. In order to convince pupils of that fact, I have often closed my eyes tightly and driven without looking at the ball after having taken up the stance and made the address. The proper swing cannot fail.”

Is Jimmy Bruen’s action related to Arnaud Massey’s “twiddly bit”?

FYI: above “cut and paste job” is not my wording…just copied it from another site.

I played on the Irish Golf Team in 1961 at the Home Internationals at Portmarnock.

I had the privilege of playing 9 practice holes with Jimmy Bruen, an Irish selector at the time. It was an astounding swing. I had seen him the previous year at Royal Portrush for the Amateur Championship, and I was fascinated. I tried this swing, and one could propel the ball great distances, control was something else. It is claimed that Jimmy practised iron shots out of divots. His course record of 66 at Royal County Down stood for decades.